Touch

3It was your tenderness—

—Toni Morrison

a tenderness so delicate

I thought it could not last,

but last it did and envelop me it did.

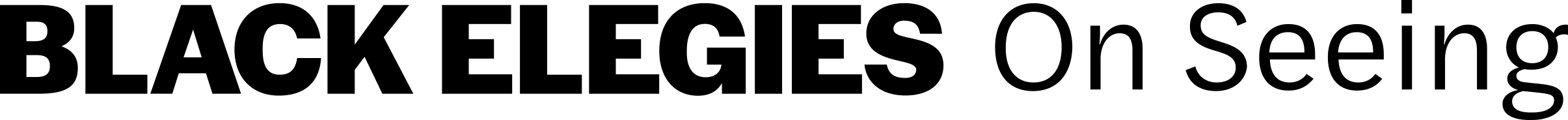

The final section of Barry Jenkins’s 2016 film Moonlight is an addition that does not exist in Tarell Alvin McCraney’s play In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue. In an interview Jenkins states: “The endpoint of the film is not the end point of the original piece. [McCraney] stopped writing at the point where Chiron is making the decision to drive back to Miami to see Kevin. So I kept going.”1 This decision to “keep going” offers the viewer not just a temporal extension of Kevin and Chiron’s story, but also an expansively resplendent coupling of haptic regard. Looks that touch, heighten, hold, anticipate, and linger. From the initial shot of Chiron, or Black, as he is known (played by Trevante Rhodes) driving with patient purpose in the direction of Kevin (played by André Holland), to the closing scene with the two men tenderly enveloped, Chiron’s head gently placed on Kevin’s shoulder, the movement is mesmerizingly slow. And we experience the culmination of loss, longing, vulnerability, desire, and anticipation in the final twenty-nine minutes of the film. Gold flickers on blue where sun meets sea.

Jenkins’s award-winning film is told in three acts, each representing a stage of the protagonist’s progression from childhood to adulthood. Act 1 is titled Little, act 2 Chiron, and the final act is titled Black. We are to follow Chiron through the labyrinth of subjectivities he experiences, from tortured child to guarded teenager, and finally hardened adult, with all of the complexities of sexual discovery mixed in along the way. The three acts visually replicate three genres of film photography: Fuji, Agfa, and Kodak, and thus appear as deep saturation (act 1), muted tones (act 2), and warm, sumptuous light (act 3).2 Act 3 functions as haptic, as the space between analog film and fingertip, fabric against skin.

In what feels akin to a collective nostalgic release, the film closes with the blue black of Little (played by Alex R. Hibbert) against the darkening sky, the night blue sky against his dark skin. And we exhale. He looks forward. He looks back. The quest is now left in our hands. In a film that shimmers, immersed in color and tone, music registers as the sonic counterpoint. Touch, then, rounds out a purely sensorial experience that Moonlight illuminates. I’m interested in Moonlight’s hapticality, particularly as it mediates the space between looking and longing for Chiron and Kevin. Within this, we have the measure of the mark of queer desire, the fragile recognition of black interiority, and the force of cinema’s still life. “There is power in looking,” bell hooks writes.3 Power. Release. Recognition. Affinity. Freedom. Affection. All this and more is set against a blue (Kevin) / gold (Chiron) background, framing the gaze and its expectant response in a cadence that flows like water on the Atlantic.

The blue tones that signal flashpoints of safety for Chiron are intermittent gestures of recognition that tell him he will be okay. The ocean is another signifier of desire, even as it is also present during the adolescent violence that marks the second act. When Black begins his journey to Kevin, the road merges with the dusk into the Atlantic where a group of children frolic with playful abandon. Chiron’s evolution, battle made and hard won, is a tautly held enclosure that necessitates time to fully uncover. And since he is also recovering from childhood trauma and practicing forgiveness, he is a figure to be handled gently and with the recognition of vulnerability that precedes him like an ellipsis in the middle of a narrative description. In his quest for haptic regard, Chiron first visits his mother at a treatment center where she is working on her recovery. She is his first relationship with the distrust of tenderness and touch, and while he was a child she produced violence and tenderness in equal measure. Black is there to retrieve and hold onto what she can offer him in in this moment that is devoid of harm. They mourn together in this scene—what could have been—and try to find a way forward without violations of trust. Black’s tears, his tenderness, sensitivity, and empathy return us to the quiet softness that he exudes in the first and second acts of the film.

“You ain’t gotta love me,” Paula tells Black as he holds back tears, “But you gon’ know that I love you. You hear?,” she asks as Black loses against the tear streaming down his face. “You hear me, Chiron,” Paula continues. “I hear you, mama, he responds.”4 The exchange between them ends with Paula apologizing for the way she failed Black. And softness returns as they embrace in a circle of blue hues—Paula’s shirt—Black’s shirt—the chairs in the recovery center—and the blue sky—that points Black in the direction of Miami and Kevin.

My interest in Moonlight as a study in stillness is twofold: It assists in a photographic endeavor of black study (still life but with a photographic trace instead of a painterly one), and stillness as sonic practice where the body holds and allows sound to fill the space. To saturate it with intention (somewhere between Tina Campt’s “thingyness” articulation in Listening to Images and Roy DeCarava’s meditations in The Sound I Saw). To this I’d like to add haptic regard, or the look that touches. For in this work I am interested in how black regard functions when the white gaze is not a part of the consideration. If we, as Jenkins insists, “keep going,” what might there be for us to see?

In the triptych display of Chiron’s progressive evolution (from Little, to Chiron, to Black) Kevin is the center of his longing and part of the mechanistic production of loss. Through each of his stages Chiron is one of few words, making his careful, slow gestures part of the nuanced offering he shares with those in his very small circle. The film opens with actor Mahershala Ali, in an Academy Award-winning role, as Juan, coaxing Little from his hiding space (where he has run to escape bullies). Juan feeds Little, counsels him, and when the child is ready, brings him home to his mother. The transformation from stranger to mentor and father figure is encapsulated in act 1 of the film, but hovers everywhere after since Juan is deceased in the following two acts of the film. This means the one man in his life, consistent with tenderness and safety, exists in Little’s early memory. The rest is longing and grief, unfolding over the film’s temporal framework. We get a sense of Chiron’s grief in the gestural motions of a trauma-infused recovery, the nuance of his corporeality.

Kevin occupies space in all three acts of the film’s narrative arc, though intimacy and absence dominate the second act where Chiron experiences desire, vulnerability, and sexual awakening alongside violence and rejection. Michael Boyce Gillespie writes: “Moonlight conjures black becoming through the accented lens of survivors, black masculinities, and queer desires.”5 This becoming is both a looking at and a looking through, a mirroring apparatus that sutures one to another in the interactive atmosphere of human engagement. I see you. I hear you. I feel you. “What to do when there really is no future,” Jafari Allen asks. “When death and nonbeing are imminent realities and not profound theorizations and understandable reflections of depressed public affect? Feel deeply. Fight to be seen for the future. And love fuck hate rage laugh work and twirl, alively, in the present.”6 Alively in the present is the quest that “keeps going” when the map bleeds off the page, offering a now that leaves room for the past and its potential future. “Aliveness,” Kevin Quashie asserts, “is inevitable because it is totality, a black world rendering that implies neither universality nor prescription . . . but instead refers to everything of being in a black world.”7 Aliveness measures the space between here, over there, and an intimate adjacency that stitches one soul to the rest of the world. Moonlight is an offering of “aliveness” in light and dark, held or set free.

Losses are multiple for Chiron, from the haunting absence of parental neglect to the aggressive and sustained bullying he receives at school. By act 2, in what facilitates a break between them, Kevin’s physical attack on Chiron sets his path forward through the violence of touch, marking the teenager with both gestures of haptic regard in equal fashion: the kiss, the punch. As we see later, Black is held together by very few threads, and by the film’s end he is coiled so tightly that the last twenty minutes of the film hold the viewer in a suspended state of anticipation.

In the extensive exchange of glances and gazes, Kevin’s intentional hold on Black is one part flirtation, and two parts curiosity. His body moves openly and freely. He is a book imaginatively displayed for the right group of readers. Importantly, Kevin endears the viewer with the comfort he has with himself. It’s a softened counterpoint to Chiron, or Black, who appears almost as a secret made flesh in the diner, hovering and quiet, and wresting time negotiating the space between longing and release. Kevin’s gestures are an offering, as if he has been waiting forever, as if he has been waiting a day. But it is Black, right at this moment, who is worthy of an extended gaze. In the temporal demarcation of their reunion, what is the measure of queer desire and how is it encased? “Now the character has to finally make a choice,” Jenkins states. “Now Chiron has to sit there opposite someone who’s actually allowing [him] the space.”8 In the scene that “keeps going,” we have a close reading of what Gillespie calls “textured beauty and blackness.” Jenkins allows this textured blackness to envelop the filmic space as part of the atmosphere of engagement that saturates as it relinquishes control.

Carl Philips’s titular poem from his book Silverchest is the control relinquished as the lover and the loved come together in the same space and time.

Unafraid is what we were, I think, and then afraid,

though it mostly seemed otherwise. I opened my eyes,

I saw, I closed. I shut them.

The usual morning glories

twist up and through banks of gone-wild-by-now holly;

crickets for song, morphos for their glamour, which

is quiet—blue, and quiet . . .

You: the dark that nothing, not even the light, displaces.

You, who have been the single leaf that

won’t stop tossing,

among the others.

For you. 9

“Silverchest” opens with “Unafraid,” and by the final line “For you,” pulls the emotive charge of desire through the entire length of the poem, reaching up and outward, like the haptic gesture of the beloved. Unafraid . . . For you . . . The “blue, and quiet” is from Little to Juan and Black to Kevin, in a concentric circle of the oceanic that signals safety and understanding for Chiron in a language he understands. Water as immersive warmth, as route and return, stands as a beacon for Chiron that he can return to in a repetition of memory making, “the single leaf that / won’t stop tossing” while he meanders through his adulthood with disciplined precision, but few comforts. Act 3 is the culmination of Black coming into being with the full measure of his humanity intact. In each scene he moves with aquatic precision, in the direction of desire. And for the sake of that desire. Because Black is steeped in the mourning arc that shaped him, because he walks with grief set against his chest, the film (and its photographic accompaniment) visually renders this hapticality with a stillness that is saturated so fully that one can feel it from one shot to another. It is this haptic quality of Moonlight that spares no subtlety, offering the viewer a look that touches in tender, careful, close caresses.

As they sit across from one another, Black flecked with gold—teeth, watch, necklace, and bracelet—the warmth of the light in the diner glistens against his skin. The diner empties out, giving Kevin and Black the opportunity to be more honest within their reunion, going past the requisite questions about how they are each doing and onto the more important matters of the heart and mind. Black glances at the door of the diner and silently decides he will say what he has been meaning to say.

Black “Why’d you call me?”

Kevin “What?”

Black “Why’d you call me?”

Kevin “I told you, man. Dude came in—”

Black “Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.”

Kevin “He played this song, man.”

Kevin rises to play the song “Hello Stranger” by Barbara Lewis and in the interim Kevin and Black exchange the all-important gazes that hold their present and past selves with all of the complicated emotional trajectories they carry. Filmic enclosures extend this tenderness in venues (restaurants, automobiles, living spaces) that allow for the portrayal of intimacy to deepen the engagement at play. After Black agrees to drive Kevin to his apartment, they continue the conversation Black began when he entered the diner with desire on his sleeve, looking for a face from the past. As they arrive outside Kevin’s apartment Black is struck by the sound of the sea, the ocean of his childhood remembrance in the visceral framework his grief has taken. Because grief is his travel companion, Black exudes the fragility of mourning embedded within a body that is perceived as hard. As hardened. The blue flame of the stovetop meets Kevin’s sea blue shirt as he re-emerges from his bedroom to continue his conversation with Black. All else is flecked with gold/yellow in the apartment, from the walls to Kevin Jr.’s crayon drawings slicing the space between the two men as they confront their past together. Their past apart. While Black confesses to building himself up anew after their last interaction as teenagers, Kevin claims that he “just kept going” since that seemed like the easiest thing to do. Kevin confesses to Black that he is about to become the man he wants to be: “It’s a life. I ain’t never had that before.” His ease and comfort is a trigger for Black, who has never achieved an ability to be a full and authentic version of himself. Not with others or alone. And Kevin’s admission that what he currently has is enough emboldens Black to make an admission of his own. “You the only man that’s ever touched me,” he tells Kevin. “You the only one. I haven’t really touched anyone since.” Kevin turns to meet Black’s gaze. To hold it there for as long as is necessary. To look with intention and interest, empathy, and care. Hard but soft, closed yet open. Fixed and malleable. Chiron says the words he has been holding onto like a secret to the only person it matters that he tell. Kevin’s tender recognition is an enclosure that fills itself with the dimensions of complex personhood rendered with care. The journey from denial to desire is an ocean. An abyss. Sun, sea, river, mountain.

In Jazz, Dorcas hears drums at a parade in remembrance of her murdered mother and father. And for her, “the drums were not an all-embracing rope of fellowship, discipline and transcendence. She remembered them as a beginning, a start of something she looked to complete.”10 As she imagines it, a fleck of wood drifts out from the leftover ashes of the fire that consumed Dorcas’s parents and “lodged comfortably somewhere below her navel,” burning still. It was an ember, a “glow” that would be “waiting for and with her whenever she wanted to be touched by it.”11 And Dorcas is ruled by the god of touch.

When Dorcas and Felice make their way to a party “led straight to the right place more by the stride piano pouring over the door saddle than their recollection of the apartment number,” they are eager to be in the communion of sight, sound, and touch.

Under the ceiling light pairs move like twins born with, if not for, the other, sharing a partner’s pulse like a second jugular. They believe they know before the music does what their hands, their feet are to do, but that illusion is the music’s secret drive: the control it tricks them into believing is theirs; the anticipation it anticipates. In between record changes, while the girls fan blouse necks to air damp collarbones or pat with anxious hands the damage moisture has done to their hair, the boys press folded handkerchiefs to their foreheads. Laughter covers indiscreet glances of welcome and promise, and takes the edge off gestures of betrayal and abandon.12

The journey from denial to desire is an ocean. An abyss. Sun, sea, river, mountain.

It is abandon they are after, and the ability to glide in and through the bustling crowd, insular in its rhythmic construction, with flesh grazing and caressing flesh. Without specifically articulating this need, the desire for touch, Jazz throbs with the silent knowing of the healing power of tenderness, of touch, and haptic regard. And so each character looks knowingly, curiously, at another, seeking out the familiar in the strange of each intimate encounter.

The flame of the ember grows, touched by the fire within, and fortified by regard that says “you are there . . . because I am looking at you . . .” in a circle of modulated understanding that deepens personal connections. Amanda Russhell Wallace’s 2017 image Ember signals the distinctive remains of the beloved when they are both here and no longer. In a burnt orange background with ghostly contours gesturing to the absence of one who is lost, Ember carries the shape of the sound of the touch of grief.

Longing and loss are yoked together in Audre Lorde’s book Zami: A New Spelling of My Name: A Biomythography. In it, Lorde reflects on her big and small intimacies. One of her earliest relationships is with Genevieve, a creative wild child Lorde meets in high school. They bond quickly and effortlessly, their shared vulnerabilities pulling them closer together as they negotiate the larger world around them, two by two. It’s clear that as Lorde reflects on this time with Gennie, this reflection highlights the would-have-been that never got to be. Genevieve takes her own life amid the turmoil of a custody fight between her parents, having threatened to do so for months beforehand. Lorde, devastated by the loss, is a swirling list of wishes that the futurity of her relationship with Genevieve held out for her:

Things I never did with Genevieve: Let our bodies touch and tell the passions that we felt. Go to a Village gay bar, or any bar anywhere. Smoke reefer. Derail the freight that took circus animals to Florida. Take a course in international obscenities. Learn Swahili. See Martha Graham’s dance troupe. Visit Pearl Primus. Ask her to take us away with her to Africa next time. Write THE BOOK. Make love.13

Zami might be described as a product of proximity and of touch. Lorde’s symbolic examination hovers between spaces and bodies. The memoir emphasizes how women—Lorde’s mother, along with others in her life including Gennie, Ginger, Bea, Eudora, Felice, Muriel, Rhea, etc.,—all form part of the center of the author’s self-made universe. This universe is a map of ntimacy and identity, with Lorde navigating the space between love and loss through her friends and lovers, her family, and her body. Lorde wrote Zami while battling breast cancer. Along with Sister Outsider and The Cancer Journals, Zami unfolds as a multilayered exploration of autonomous existence. Zami is, at its center, a quest for connection that is facilitated through touch. In it, Lorde negotiates the difficult space between love and profound, repetitive loss. Her river. Her mountain. Amber Jamilla Musser writes: “Lorde’s insistence on having sensuality, desire, woman loving, and politics meet in the same space is deliberate. The radicality of insisting on a language of sex for queer black female bodies rescripts the ways that coalition might be enacted; it renders the sensual political in large part because this queer feminine . . . offers a challenge to the epistemologies of sexuality.”14 Lorde locates her quest as a journey through touch—tentative, fragile, passionate, tortured—draped over the consequential years of her life. Published two years after The Cancer Journals, Zami pulls the disparate pieces of Lorde’s corporeality into a cohesive, erotic, intimate whole. Understanding her body in its state of cancerous inflection point, Lorde reflects on her relationships in order to acknowledge, like Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, what has made her who she is—dissonance and assonance—as she grapples with all she has lost and all she has learned. Lorde’s poetry never leaves her, and neither does her insistence upon her connections, the life pulse of ability to “do language” and conjure the dead. “To be sensual, I think,” James Baldwin wrote, “is to respect and rejoice in the force of life, of life itself, and to be present in all that one does, from the effort of loving to the breaking of bread.”15 Because the reader moves with her on her journeys, from poetry to prose, fury to passion, we bear witness to Lorde’s command of word and deed as she endeavors to make herself known.

Rebecca Hall’s filmic adaptation of Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel Passing also traverses the space between saturation and control for Irene (played by Tessa Thompson) and her childhood friend, Clare (played by Ruth Negga). The film beautifully captures much of the sexual tension imbued in the novel, as passing, as metaphor, opens a series of transgressions for two black cosmopolitan women who find themselves betwixt and between America’s peculiar one-drop color line. Clare passes for white in this world, and Irene, for the most part, does not.

In the lush landscape of the film’s framing, Irene’s quest to move through Clare manifests itself upon their first encounter after so many years apart. Clare is looking and Irene is glancing. Clare holds her gaze until Irene can no longer look away. Her body. The poise. The deep breathing. The look that does not stop looking. James Elkins writes, “In life a gaze challenges, it inquires, it takes pleasure and it asks for a response.”16 And so a dance of call-and-response is an invitation between two people who know the danger and look anyway. The loss of intimacy between the film’s two protagonists is a callback to a past where they could coexist with their desires exposed to the light. In the furtive glances at the film’s center, Hall directs the line of sight from the heart pulse out, as Clare and Irene attempt to return to the world they left behind. Because I am looking at you . . .

Using the brim of her hat as a shield, Irene sits alone at the Drayton, having stopped for a cool drink in an establishment she knows is marked for whites only. She is careful, poised, and hypervigilant concerning her surroundings. Observing all around her—a woman whose body is visually obscured, a couple performing the ritual of public affection, and two elderly women sitting together, one sipping tea while the other gazes off into the distance. The two women are proximate to each other but seemingly worlds apart—as detached as two gentle yet opposing forces navigating the same space. Irene’s eyes continue to meander. They move across and back, past the seated figure holding Irene in her elegant gaze. Clare. Irene sets her eyes downward, apprehensive and tentative. Clare’s eyes do not let go. Irene rises to leave, likely mistaking Clare’s gaze for racial scrutiny. “And there was about her an amazing soft malice,” Larsen writes, “hidden well away until provoked.”17 Irene provokes devoid of intention, for it is the sight of her, the surprise reunion that sends Clare’s impulsive fire to full flame. Across the table from her childhood friend, Clare reaches for Irene’s hand, touches it, while Irene instinctively pulls away. Clare lights a cigarette—her fire, her flame—and prods Irene’s hesitance. “Well, we can see lots of one another these days that I’m here, can’t we?” Irene isn’t so sure.

Passing replicates the haptic quality of black-and-white photography alongside the aesthetic enclosures that signal intimacy and interiority. Hall’s rendering of the slippages and constraints of identity brings a visceral tacticity to Irene and Clare’s reunion. After the series of gazes and glances between the two women, Clare glides over to Irene’s table with intention.

Clare “Pardon me. I don’t mean to stare, but I think I know you.”

Irene “I’m afraid you’re mistaken.”

Clare “No, of course I know you, Rene. You look just the same. Tell me, do they still call you Rene?”

Irene “Yes. Though no one’s called me that for a long time.”

Clare “Don’t you know me? Not really Rene?”

Irene “I’m afraid I can’t seem to place . . . Clare?” 18

From “Why’d you call me?” to “Don’t you know me?,” longing floats in a cinematic spiral that leads, dangerously even, in the direction of desire. Clare and Irene’s reunion is filled with intensity, caution, trepidation, and fascination. Though their collective hunger spills out to separate results and possibilities, both women are encased in the respectable compartments that keep them from holding one another close. The film manages the fraught boundary between race, sexuality, geography, and desire by using Irene and Clare as magnets unable to look away from each other once their eyes meet. Touch, though risky for both, is nevertheless attempted within the confines of their bodies as separate, as same.

Both Passing and Moonlight possess configurations of analog photography, and in this they are drawing on the aesthetic referral of photography’s haptic materiality. “If a photograph’s frequencies are a potential route to a different kind of knowledge,” Michèle Pearson Clarke writes, “a knowledge generated by feeling—then perhaps the rough texture, the ‘thingyness’ of an analogue photograph of Blackness produces an intensity of vibrations to which we can more easily attune.”19 This ability to attune is accentuated by both motion and stillness. And for both films, it is a study in the gravitational pull that is imbricated by longing as loss. Longing as release.

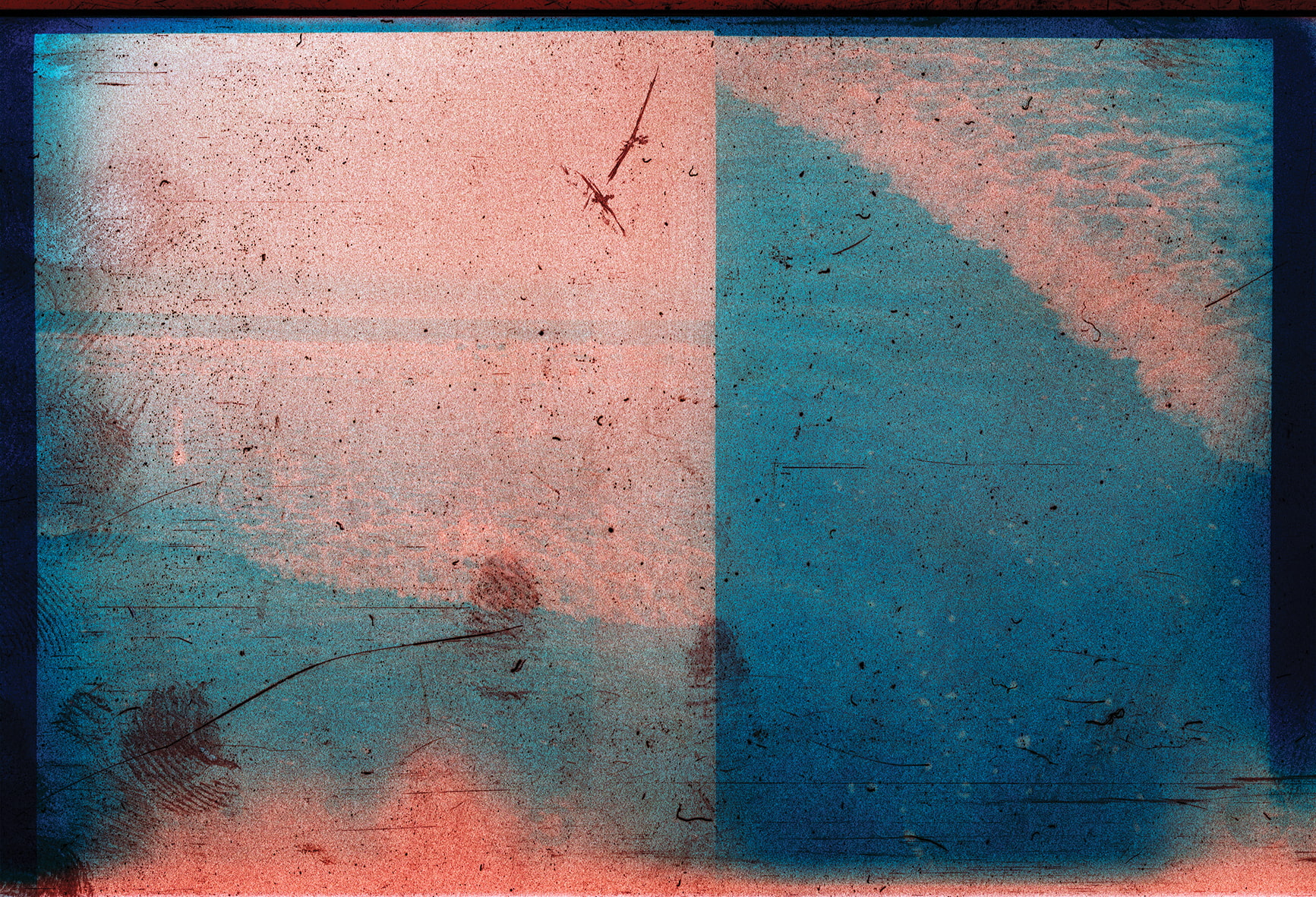

Dell Marie Hamilton’s Emulsions in Departure features fingers on photographic print, painted with haptic regard and vigilant longing. Forming part of Hamilton’s early work, Emulsions in Departure is a film/photography interplay that uses the imprint of Hamilton’s fingers to provide texture and tone to the materiality of loss. Of longing. A fortunate accident while scanning images produced the series, which has the visual effect of merging all of the elements into a series of photographic prints. Earth, wind, fire, and water converge here, as constitutive constructions of the black diaspora separated by oceans, rivers, and seas. Hamilton’s abstraction is also a submersion, deepening the discourse of loss that carries itself across terrains in order to render grief visible even if it is only partially legible to others. With the title Emulsions in Departure, Hamilton engenders an atmosphere of separation amid convergence, where mourning often resides. Referring to the work as “melancholy,” Hamilton’s use of texture and color creates a parallel engagement wherein an architecture of grief flows outward and provides a visual dispersal that coheres around the disparate subjectivities of black life. Emulsions signify the touch of liquid on liquid, mist on mist, in order to bond and separate with intention. This touch on touch is put in the service of haptic layering for Hamilton, who mixes and merges her art process so that it follows her aesthetic design. In her effort to bind memory to image making, Emulsions brings the anxiety of separation into a tactile canvas of artistic management.

Departures saturate Jafari S. Allen’s There’s a Disco Ball Between Us: A Theory of Black Gay Life, and it is at times overwhelming to place in context, in time. In the archive of black grief and black artistic production there is the “material and/or ethereal evidence—burnt shards, traces of the violence: your playlists, meeting agendas, eviction notices, and the first draft of your grant proposal” to reference the work that is done and that is yet to be done.20 The work yet to be done includes that of the haptic retrieval, which can attempt to measure losses we are just now beginning to calculate. Reverberations of HIV/AIDS haptic refusals drift into more contemporary discourses of COVID while detaching the latter from an explicit marker of sexual identity. “Many of the scenes and many of the people who made the still-significant long 1980s fierce have already passed,” Allen writes. “My preoccupation, pace Morrison, is that it seems they have also been passed on in too many ways.”21 If “this is not a story to pass on” then it is also a not a story to “pass on,” and this is how we can hold the gaze on offer and return it with understanding and communion.

Carrie Mae Weems’s 2016 video People of a Darker Hue brings together images and archival sound clips with Weems’s melodic voice-over in order to compel the viewer in a mesmerizing sweep of black presence and black being. Weems melds her artistic concerns into a sight/sound navigation bound by touch. With dozens of mostly black subjects moving about on city streets in the first section, the viewer is immersed in a swirl of slow-paced migration that intimates slow-paced racial progress. A voice-over by Paul Robeson duplicates the sound of black mourning amid black revolution as Robeson delineates the point of his navigational trajectory:

I am today giving up my concerts for two or three years to enter into this struggle at a very . . . it’s what I call getting into the rank and file struggle of my people for full citizenship in these United States. So I won’t be singing except for the rights of my people for the next couple of years. No pretty songs gentleman, no pretty songs. Time for some full citizenship.

Understandable, the attempt of the enemy was to cut off the progressive people from the great masses of the Americans. In my own case it was to cut me off from the Negro people from whom I was born. Imagine, somewhere somebody says, I, born a Negro, that because of my beliefs, my fight for peace, my fight for friendship between nations, my fight for the complete liberation of my people, that somewhere I am not an American. That I should be cut off from the very people from whom I was born. 22

Weems’s voice enters, overlapping with Robeson’s. Set against a blue background and the image of a single figure running in place, we hear Weems again present a series of statistics (“he was 39 . . . she was 25 . . . she was 34 . . . he was 27 . . . he was 12”) until they merge in a repetition that signals the unrelenting violence of white supremacy. Out of this auditory enclosure comes the visual duplication of people engaged in the act of mourning even as the acts they have assembled to protest continue. Midway through the video we see black subjects, placing open hands against their chests, eyes closed, and collectively grieving the lives lost that Weems outlines in her vocal arrangement. The scene is split with archival video clips of recorded murders from Laquan McDonald to Philando Castile and Eric Garner. For LaCharles Ward, “acting as visual transitions, so to speak, the protestors return with clinched fists hitting their chests as to signal the continual outcry against each act of violence.”23 It is this visual act, then, that provides the heartbeat of the video, bringing the gesture of intimacy of touch toward a collective goal.

As Weems highlights the work of communion in witnessing and participates in an artistic laying on of hands, People of a Darker Hue also succeeds in modulating the fragile space between one black subject and another in the arena of external world racializations and the violence that greets those who are rendered available to indiscriminate extraction. The images remind the viewer that the space between one and another is a vulnerable space, a fragile liminality that asks for vigilance in the face of black exposure to danger. For as Weems states:

They were no strangers to sorrow. Time and time again, the man was rejected, the woman was denied. A man was killed, the body laid in the open, uncovered and exposed. Women wailed and men moaned. For reasons unknown, I saw him running. I saw him stop. I saw him turn with raised hands. I heard a shot. I saw him fall. For reasons unknown, I rejected my own knowledge and I deceived myself by refusing to believe that this was possible.24

People of a Darker Hue, Weems seems to say, cannot separate themselves from the limited frame of seeing and being seen exhibited by others. They, too, must participate in haptic regard, and do so with an emphasis that returns the body back to itself, extends the contours of recognition, and offers haptic testimony to all and any who’ve been lost.

Jazz ends with the unnamed narrator ruminating on the contours of love, of touch, that animate her ability to provide testimony to the arc of intimacy she witnesses and of which she wants to take part. In this, she functions as a representation of collective desire, as she endeavors to release herself of the burdens of desire. Of Joe and Violet Trace, she admits:

I envy them their public love. I myself have only known it in secret, shared it in secret and longed, aw longed to show it—to be able to say out loud what they have no need to say at all: That I have loved only you, surrendered my whole self reckless to you and nobody else. That I want you to love me back and show it to me. That I love the way you hold me, how close you let me be to you. I like your fingers on and on, lifting, turning. I have watched your face for a long time now, and missed your eyes when you went away from me. Talking to you and hearing you answer—that’s the kick.

But I can’t say that aloud; I can’t tell anyone that I have been waiting for this all my life and that being chosen to wait is the reason I can. If I were able I’d say it. Say make me, remake me. You are free to do it and I am free to let you because look, look. Look where your hands are. Now. 25

Now. Now. In the immediacy of the haptic, in the “dark that nothing, not even the light, displaces,” is the doubling elegy of longing and loss. Each character in the novel navigates this loss and longing differently. From Violet who flails trying to reach back to the person she could have been, to Joe who embraced his former training as a hunter to disastrous results, to Felice who settled into her dismissive trace of mourning for a friend. Alice Manfred tried to restrict her way out of the danger that accompanies an acknowledgment of grief. And she tried to restrict her niece Dorcas so that eventually the apartment they shared together began to close in on Dorcas like the lid of a coffin. Morrison’s novel is a reminder of the movement that grief takes, who it holds and what it won’t let go. And the book invites the reader in from the very beginning of the opening (“Sth, I know that woman”) to the final line, “Now.” It gestures toward the grandeur of the ease of understanding that intimacy retrieves if you let it. And the immediacy of the visceral embodiment of a love that is there “for you.”

Note 1

Michael Boyce Gillespie, “One Step Ahead: A Conversation with Barry Jenkins,” Film Quarterly 70, no. 3: 55.

Note 2

James Laxton, “The Photographic Inspirations Behind Moonlight, 2016’s Best Picture,” interview by Andrew Strecker, November 21, 2023,

https://www.lensculture.com/articles/moonlight-cinematography-the-photographic-inspirations-behind-moonlight-2016-s-best-picture, archived at https://perma.cc/BY8Q-PQAS.

Note 3

bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Feminism and Visual Culture Reader, ed. Amelia Jones (New York: Routledge, 2002), 94.

Note 6

Jafari Allen, There’s a Disco Ball Between Us: A Theory of Black Gay Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022), 71; emphasis in original.

Note 7

Kevin Quashie, Black Aliveness, Or a Poetics of Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 23.

Note 13

Audre Lorde, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name: A Biomythography (New York: Random House, 1982), 97.

Note 14

Amber Jamilla Musser, Sensual Excess: Queer Femininity and Brown Jouissance (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 175–176.

Note 17

Nella Larsen, Passing: A Norton Critical Edition, ed. Carla Kaplan (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2007), 6.

Note 22

Transcription: People of a Darker Hue, 2016, McMullenMuseum.bc.edu, https://mcmullenmuseum.bc.edu/exhibitions/weems/transcriptions/people.html, archived at https://perma.cc/A3YP-SQ9E.

Note 23

LaCharles Ward, “‘Keep Runnin’ Bro’: Carrie Mae Weems and the Visual Act of Refusal,” Black Camera 9, no. 2 (Spring 2018): 82–109, 98.