Sight

1all breath travels out and up disperses

—Vievee Francis

and

cannot be followed.

Ink and beeswax on paper conspire to envelop the viewer in a communal endeavor of palpable loss. Toby Sisson’s Black Tears series engages the work of release in the production of mourning. Each tear is a 7″ × 5″ rupture in the linear history of black progress. They collectively represent the effort to encapsulate black grief into a legible text—that which provides a space of contemplation for the multiple losses sustained by black subjects over time. Sisson was compelled to create the artwork to address the extra-juridical killings of black subjects covered in the media, from Trayvon Martin to Mike Brown, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Tyre Nichols. Black Tears is also an extension of Sisson’s meditation on James Baldwin’s book Jimmy’s Blues and Other Poems. In this, she is drawing on a word/image interplay that Baldwin offered during his long career, one that privileges explorations of the burden of antiblackness as it affects the lives of black people and black communities. Sisson is an abstract encaustic painter who typically works with large-scale constructions on canvas. Black Tears brings her concerns from abstraction to figuration in order to address black pain.

Black tears. In a letter sent to W. E. B. Du Bois in 1905, a graduate student at Clark University in Massachusetts queries, on behalf of his class, about the “subject of crying as an expression of emotions.” Specifically, what the students really “desire to know” is “whether the Negro sheds tears.”1 This question engenders others: Do black people mourn their dead? Feel pain? Have emotions? The letter arrived two years after Du Bois’s monumental book The Souls of Black Folk was published. In it, Du Bois went to great pains to illustrate what survival has cost black Americans. He opened each section of Souls with sorrow songs as epigraphs, to express how devastating the history of slavery in the United States has been for its victims, and how hard they have worked to manage the damage caused. As a visual experiment in cumulative trauma, Sisson’s Black Tears grow and replicate—from a few dozen, to nearly one hundred, to over four hundred (and counting) individual and distinct tear drops that seek to reckon with the violence that often accompanies being black and alive. They represent black folks with souls, who exist and bear witness, who strive and mourn. Who shed tears.

Black Elegies is an opening onto the expansive artistic black world tasked with expressing collective grief while also grappling with terrors that continue unabated. I begin the first chapter of Black Elegies with Sisson’s Black Tears to consider the intentional work of artistic production meant to tell us something about mourning, something about seeing. Tears are a multifaceted mechanism of release formed by the eyes and they assist in ensuring that oxygen and nutrients hydrate the surface of the eye. This clear liquid fills the eye until it overflows into tears that a group of white students in 1905 were unsure black people could shed. So we will elegy here, in this place of profound misrecognition until the matter of black lives is made visible.

Four Men

Four men stand in close proximity to one another, with varying degrees of visibility. Parts of faces are obscured, and what is not obscured holds the viewer in a space of sorrow and fury. Tina Campt writes in Listening to Images: “The choice to ‘listen to’ rather than simply ‘look at’ images is a conscious decision to challenge the equation of vision with knowledge by engaging photography through a sensory register that is critical to Black Atlantic cultural formations: sound.”2 Antiblackness has a shadow, and the demarcations of dispossession that augment its terrain are photographically contingent. For the moment I want to explore this contingency for the urgency and longevity it contains in Roy DeCarava’s photograph Four Men and Toni Morrison’s novel Jazz. The texts, taken together, are in conversation with expressions of grief both visible and invisible; expressions that flow like tears centered in a photographic print.

“A single exposure, a moment.”3 Outside a Harlem church Roy DeCarava photographs four black men emerging from a memorial service. The service is for the four girls killed in a church explosion in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. With this image, according to DeCarava, “there is a kind of movement . . . it is a movement forward, back, and then side to side.”4 With his poetic investments in the cadence and the rhythm of black visuality, the images he creates require more time to take in. You have to listen to them. Left lingering in the center of the frame is a face of concern and near-distraction. He seems to be elsewhere, perhaps trying to take in all the marked violence that a proximity to blackness engenders. Maybe in this moment he thinks of relatives, loved ones. Perhaps he is transfixed by a feeling of helplessness and continued vulnerability. There are tears welling in his eyes and they seem about to fall. He holds them, and the photograph is suspended in this space. A forever set of tears about to fall devoid of catharsis. In essence, this photograph, close-cropped and with duplicated tonalities, is grief in the frame.

Toni Morrison centers her sixth novel on this kind of “single exposure,” this “moment” that DeCarava captures with his image. A photograph sits on a mantel, facilitating the process of mourning for a married couple, Joe and Violet Trace. This photograph is a tangible object of memory making and it is the image of a dead girl, who is not so in the photograph. Morrison describes the photo of Dorcas, the teenager loved and then murdered by Joe Trace, as one that was “not smiling, but alive at least and very bold.”5 In this, Morrison challenges Roland Barthes’s assertion that a photograph is always already a “spectrum” of death. In Camera Lucida, Barthes writes: “because the word retains, through its root, a relative to spectacle and adds to it that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead.”6 Morrison’s dead do not return as much as they remain, hovering between “alive . . . and very bold,” in silent communication with the living.

Jazz is the story of the Great Black Migration, the journey in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century from the rural South to the cities of the North. It is the sound of the wind that carried all those people and their dreams, desires, fears, and creative impulses, and held them together in something resembling a black melody—part sorrow song, part blues, part jazz and rock and roll. If African American cultural productions are practices in the sensorial, they ask us to participate in the endeavor, a dedicated acknowledgment of the resonance of sight and sound, the ever-deepening conversation that blackness opens out into the world. That conversation is filled with pain and its spontaneous release.

In Morrison’s Jazz, Violet Trace attempts to mutilate the corpse of her teenage rival, traveling to Dorcas’s funeral service to communicate with the once-living. It is Violet’s repetitive obsessive insistence (she begins spontaneously visiting Alice Manfred, Dorcas’s aunt) to understand her circumstance, and this leads to Violet “borrowing” the photograph of Dorcas in the first place. She puts it in the carefully ordered home where she lives with her husband, Joe. Morrison writes:

Back up there on Lenox, in Violet and Joe Trace’s apartment, the rooms are like the empty birdcages wrapped in cloth. And a dead girl’s face has become a necessary thing for their nights. They each take turns to throw off the bedcovers, rise up from the sagging mattress and tiptoe over cold linoleum into the parlor to gaze at what seems like the only living presence in the house: the photograph of a bold, unsmiling girl staring from the mantelpiece. If the tiptoer is Joe Trace, driven by loneliness from his wife’s side, then the face stares at him without hope or regret and it is the absence of accusation that wakes him from his sleep hungry for her company. No finger points. Her lips don’t turn down in judgment. Her face is calm, generous and sweet. But if the tiptoer is Violet the photograph is not that at all. The girl’s face looks greedy, haughty and very lazy. . . . It is the face of a sneak who glides over to your sink to rinse the fork you have laid by her plate. An inward face—whatever it sees is its own self. You are there, it says, because I am looking at you. 7

Dorcas’s image, “the only living presence in the house,” is both “calm, generous, and sweet,” “greedy, haughty, and very lazy.” In short, the image reflects the three-dimensional complexity involved in being human, and the contradictory alliances people experience mourning the death of another. In this manner, the photograph (and its attendant gaze) propel the narrative forward, through the couple whose mantel is occupied by the haptic, hypnotic, shape-shifting register of a dead teenage girl whose image says, “you are there . . . because I am looking at you.” The multiple acts of looking and looking back organize the novel through the very process of improvisation that Morrison deploys. In this, Dorcas functions as the constant, allowing Violet and Joe (and eventually Dorcas’s best friend Felice) to add their chords to Dorcas’s. The song is different each time but utilizes a familiar refrain. And so, the novel shifts its directional point of view in order to emphasize the visual/choral/aural properties of black cultural production. The photograph is a centralizing motif of movement amid stasis, and allows us to grapple with loss, and its racialized disavowal.

If we think about Jazz as the elongation of photographic development, Dorcas comes fully into being only through an unspoken but collective ethics of care that the narrative mediates through each of the characters. This makes plausible the sustained attention to her memory (in sight, in sound) that keeps Dorcas in the space of the present. “Two or three times during the night, as they take turns to go look at the picture, one of them will say her name. Dorcas? Dorcas. The dark rooms grow darker: the parlor needs a struck match to see the face.”8

Here’s the thing about a darkroom or a dark room: the mechanics of the space necessitate time—to allow the iris to expand and let light enter the eye. And so Dorcas is developed in a time-released manner by the man who shot her to death and the woman who journeyed to her funeral in order to “see the girl and cut her dead face.”9 In this, the first chapter of Black Elegies, I am interested in the register of photography in Jazz, the construction of the elegy in jazz music, and the production of mourning that is highlighted by both. I am also interested in the back story to Dorcas’s photograph. In her foreword to Jazz, Morrison says, “I had decided on the period, the narrative line, and the place long ago, after seeing a photograph of a pretty girl in a coffin, and reading the photographer’s recollection of how she got there.”10 A photograph orients Morrison’s writerly eye toward James Van Der Zee’s 1978 Harlem Book of the Dead, and Jazz unfolds organically from there. The novel presents movement as the singular organizing force of black Americans, and provides a cartography of that movement that places music in communion with bodies. Our unnamed narrator tells us something important about Joe Trace and why he was considered thoughtful and charismatic by the women in the city: “they liked his voice. It had a pitch, a note they heard only when they visited stubborn old folks who would not budge from their front yards and overworked fields to come to the City.”11 Joe Trace sounds like home, and home in Jazz is a longing that has little to do with the temporal location of where people live or how they love. How loss looks or how it sounds. A pitch, a note.

Alabama

It is said that John Coltrane’s 1963 song “Alabama” is structured to imitate the cadence of Martin Luther King Jr.’s eulogy, delivered on September 18 of that year, for the four girls murdered in the city of Birmingham, Alabama. “These children, unoffending, innocent, and beautiful,” King begins, “were the victims of one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity.”12 Saxophone to bass, piano, and with Elvin Jones on drums, Coltrane offers us the sound of collective mourning. Mourning in plain sight, where violence meets a refusal of full citizenship while simultaneously engendering enclosures of black subjectivity. Jazz, the music, reconciles improvisation amid mournful wails with the possibility of resolution. “Alabama” depends on the subtleties of the unsaid, the sound of this recognition in an arc of collective emotion. Christina Sharpe writes, “In the midst of so much death and the fact of Black life as proximate to death, how do we attend to physical, social, and figurative death and also to the largeness that is Black life, Black life insisted from death?”13 Coltrane might say that we must listen to it. “And so my friends, they did not die in vain,” King continues in his eulogy. “They say to us that we must be concerned not merely about who murdered them, but about the system, the way of life, the philosophy which produced the murderers.”14 With “Alabama,” it is not enough to simply grapple with loss, one must also commune with it, make a space at the table for grief, see it, touch it, and listen to its demands. Coltrane’s elegy encompasses the negotiation of double consciousness that W. E. B. Du Bois presented as a particularly fraught black experience.

Four African American men visually negotiate the space of loss in a circular double consciousness that extends beyond the frame. If we stay here, though, we can hear the measure of Coltrane’s subtle arrangement—the movement and the arc, the depth of his auditory field. “The seriality of the untimely forfeiture of black and brown lives . . . has become an urgent refrain that echoes backward and forward in time,” Campt writes.15 This refrain and its duplication demarcates the photographic space as one imbued with a poetics of loss that must be traversed carefully.

Musicians and dancers are prevalent in DeCarava’s photographs from the 1950s and 1960s. He is seeking in that moment the thing they have in common with photography, how “in between that one-fifteenth of a second, there is a thickness.”16 This “thickness” is a visual demand on his part, and a measure of the absolute lushness of his images. This lushness exists whether the subject is clearly rendered and engaged with the photographer, is tangential to the framing of the photograph, or is an inanimate object. He is as drawn to architectural sites as he is to portraits of strangers in the street. Some of his images ask the viewer how much they believe it is their right to see, or they force an engagement that takes the power of a dark space as a photographic right. In Darby English’s book How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness, he laments the art world’s “tendency to limit the significance of works assignable to black artists to what can be illuminated by reference to a work’s purportedly racial character.”17 In the case of DeCarava, the photographer’s lifelong attempt to render visible the aesthetic quality of his subjects was limited by a photographic history of racial containment, one unable to release black subjectivity from the framework of corporeal destruction. Using black-and-white photography but insisting on the more fluid range of gray, DeCarava’s images emote a lyrical momentum, allowing the viewer to see the world how he sees it, from a darker tonal place. His is an artistic practice that says I see you, then I hear you in a photographic print.

When people speak of Roy DeCarava’s photographs, they speak of tonalities, endless grays, fissures of content and form heavily dependent upon a unique aesthetic vision. One that does not fear gray matter, and one that isn’t interested in the stark contrast of blacks and whites dominating photography during the second half of the twentieth century. He knows that most of us live in the gray zones, spaces less regulated, and under recognized. But what if we were to linger there . . .

Dorcas’s image sits on the mantel in the Trace home, and allows the couple to mourn through the multimodal register of loss. Home. Family. Love. Need. The name, Trace, connotes the production of photographic memory. John Berger writes: “Unlike any other visual image, a photograph is not a rendering, an imitation, or an interpretation of its subject, but actually a trace of it.”18 Violet and Joe must “trace” the photograph back through time in order to move forward; they use Dorcas’s image to do just that. Morrison produces in the construction of Dorcas’s memory the inexplicable mystery of kinship that binds one person to another whether or not the ties that bind them are familial, intimate, or facilitated through the image of a stranger staring back with eyes that hold no expectation of the viewer or every expectation. This is the secret embedded in the photograph. Any photograph. It is a way of seeing that is here and not here. Past, present, future. The process of mourning for Violet and Joe, Alice Manfred, and Felice is atemporality of jazz. “He has double eyes,” Felice says of Joe Trace. “Each one a different color. A sad one that lets you look inside him, and a clear one that looks inside you.”19 Though not visible, Violet has double eyes as well. Her only folly is that it took so long to allow the “sad one” to be seen by others.

The reader is allowed inside this space of collective mourning as well, since Morrison takes great pains to bridge the Great Black Migration with its attendant sorrows: separation from family, the violence of white supremacy, removal from the land. Is improvisation an attempt to both reclaim and transcend that land? Can it mark the visible in ways that allow for a reckoning with loss? Toward the end of the novel our unnamed narrator, observant, and seemingly everywhere and nowhere, offers a new description for the long-married Joe and Violet: “When I see them now they are not sepia, still, losing their edges to the light of a future afternoon. Caught midway between was and must be. For me they are real. Sharply in focus and clicking. I wonder,” the narrator continues, “do they know they are the sound of snapping fingers under the sycamores lining the streets?”20 In the “not sepia” “sound of snapping fingers under the sycamores” there is an acknowledgment of movement, landscape, rhythm, and the futurity of self-discovery, all of which takes place inside an enclosure of loss. I see you . . .

DeCarava imbues an intimacy of mourning with his photograph of the men, one that registers the extension of their concern beyond geography, age, gender, or class. The four men, then, do not occupy space left open by the murder of the four girls in Alabama. They instead supplement the politics of collective mourning to encircle and instruct. Here, in the auditory configuration of photographic stillness, DeCarava’s pause is also a riff, an improvisation, and a coda. The photograph is a study in affect. The movement from left to right gives the viewer the opportunity to move across each face with intention, to think about proximity and refusal, and consider the costs of racial progress.

John Tagg writes: “There is a dark room. A shutter opens. The room is flooded with light that threatens to bleach the interior white.”21 Morrison’s dark rooms are embodied relations, developed in close proximity to the tactile objects that facilitate memory making. They are both sight and sound, practices in the sensorial that resist a photographic death and instead opt for an auditory life. These elegies attempt to address the collective traumas black people experience while they grapple with citizenship so fraught that its very visibility is a problem. DeCarava cloaks this visibility in tonal proximity: photographer to subject, viewer to image. DeCarava’s wish, encased in a circular refrain of black movement and the containment of space, is envisioned as an articulation of meaning brought about through deep looking and deep listening. Necessary for emotive release.

The drumbeat that closes out the first song from Ibeyi’s sophomore album Ash pulls the listener into the heart pulse of the album’s spiritual concerns. These concerns range from the deeply meditative to the resistant, to the haunting loop of repetition that signals emphasis. What we hear in the atmospheric release of the song “I Carried This for Years” pulls from the gravitas of loss to introduce us to something new in one minute and thirty-five seconds. The syntactical interplay—I . . . Carried . . . This . . . for Years . . .—supposes the listener is joined in the particularities of elongated grief, like a sorrow song that goes on forever. “I Carried” alters the usual conjugation of the verb “to carry” from present perfect to past participle. From “I have carried” to “I carried.” It’s subtle but visceral, like a series of teardrops on a wall with no end. “Years” is the temporal fixation that blackness will not cleanly abide. So the timeframe morphs into decades, quarter centuries, hundreds of years, and, potentially, eons. The load, then, that is carried becomes central to an understanding of who we are and why this matters. What you carry is both what is yours and what others have burdened unto you, regardless of intention. What might it cost to put our burdens down? And where?

What you carry is both what is yours and what others have burdened unto you, regardless of intention. What might it cost to put our burdens down? And where?

“So a theme in your work is listening,” DeCarava is asked in an interview by Ivor Miller. “Absolutely,” DeCarava responded. “Seeing in the same way that one listens. To listen means to concentrate and focus on something that you are listening to. Seeing is the same thing. And waiting. Time is more important than all of that.”22 The photographer has stated that his artistic concern is with people: “What they do and what they feel and what they touch and what they leave behind.”23 Within the tremendous range of subject matter and the deeply meditative productive deployment of his photographic gestures we can see an artist intensely devoted to a particular way of seeing; to a particular manner and mode of photographic practice that does not dictate, but rather uses ambient light and sound to illuminate an already-present engagement.

Men, women, and children glide between the sky and the sea, disappearing into a space that is at once submerged and elemental. Jeannette Ehlers’s mesmerizing video Black Bullets somberly commemorates the Haitian Revolution as the forward movement of people almost relinquished to history. Anonymous figures move across the screen slowly, effortlessly, as if assisted by only by air and ocean. They move from the left side of the frame through to the right, as they collapse into an atmospheric undertow that has the capacity to clear a path that allows something new to emerge. Filmed on location at the famous Citadel in Nord, Haiti, Ehlers, a Danish/Trinidadian artist working in multiple genres, turns her attention to the absented presence of the Haitian Revolution in diasporic memory. Faith Smith locates Haiti’s “sovereign maneuvers” through a series of successful “emancipatory gestures” that produce “harsh retaliation” in order to stamp out resistance lest it lead to other calls for freedom.24 Ehlers’s subtle auditory dissonance works to illuminate the clash of history as a convergence point that Haiti represents. This convergence point is commemorated in acts of resistance that remind the black diaspora of its geographical navigation, so there is a way to mourn while continuing to breathe the air of autonomy. “I’m very much drawn to the body,” Ehlers has said. “That’s my material in a way. . . . I’m trying to produce monumental knowledge about our history and our presence.”25 Ehlers’s collaborative sculpture I Am Queen Mary was created with La Vaughn Belle to represent the Danish relationship to slavery’s legacy (Belle is from the U.S. Virgin Islands [formerly known as the Danish West Indies]. The two artists created the monument, the first to represent a black woman in Copenhagen. Ehlers and Belle, invested as they are in speaking back to history, make visible the sacrifices forced on black subjects who rarely get to imagine the other side of subjugation. Black Bullets retrieves the ethos of resistance as a slow-paced, somber, rhythmic glide into the liner notes of history. On the way each of the figures imprints the space with its individual and collective grace, inspired by the glory of freedom. “Black bullets” facilitate a weapon that, combined with speed and precision, can do immeasurable damage to the power structures aiming to refuse their sovereignty. Ehlers invokes the heaven and earth topography that merged in order to wade through water and envelope the sky. So that freedom could encompass the first black republic in the western hemisphere. As the stream of bodies dissipates collectively (in pairs and trios) or individually, the viewer is tasked with the work of witnessing, of commemorating, and of grieving. In its most elegiac formulation, it is the funereal processional that marks the bodies that the revolution has claimed on its way to free itself from the perpetual enslavement imagined by others. Here, Ehlers offers the repetition of revolution in a loop, or a circle. One that marks the visible with the glimmer of anonymity that casts the sky and the sea as libratory elements marking freedom as a thing “needful as air” and deserved by all.26

A voice reaches out from beyond the sonic accompaniment of bass, cello, and drums. Three words are released into the aural atmosphere: I am free. A statement. A command. A lament. A conjuring. A love story. I am free. Joined alongside Ehlers’ film, the UK soul/funk/R&B ensemble Sault gives an offering with their 2022 gospel song “I Am Free.”27 The song opens Sault’s Untitled (God) album and is meant as a route through the gravity of black life that must eventually lead to freedom as a state of release. Sault’s mysterious emergence into the music scene is central to this ethos. A largely anonymous collective that began releasing music in 2019, Sault has almost a dozen albums to date. They range from protest songs to disco, funk, R&B, and gospel. With the ethereal “I Am Free,” there is the replication of the slave spiritual, or sorrow song, with sparse lyrics, repetition, and modulation in the emphasis of the lyrics. How many ways can one declare their freedom? If Black Bullets is a sorrow song made visual, “I Am Free” is the sonic accompaniment that forms shape with each declarative utterance. Shape made form in the fleshy thickening of the arc and the reach of ecstatic freedom. And for the largely anonymous group of Haitians making freedom the centerpiece of their existence in the years beyond French colonization, the song beckons, calls, and responds. “I Am Free” takes a funereal undertow and drives it forward with speed that matches the very simple intention—to be free. It moves in tempo and pace with Black Bullets, as if it were its second soundtrack, and therefore merged with the film organically.28

Untitled (God) was released November 2022 as Sault’s eleventh studio album. “I Am Free” is the opening track, thereby setting the tone for the rest of the album. Sault released five albums in 2022, exhibiting an eclectic range and remarkable depth of purpose and intention. If black love had a unifying musical sound, it would be Sault. Untitled (God) is meant as an offering to exalt the human spirit and take it to the nexus of illumination. Faith is love. Trust is love. Beauty is love. And yes, black is love. So Sault leans on those collective identities that tie, that bind, and invests in them sonically, so that something otherworldly can appear. Jeannette Ehlers’s Black Bullets is the something otherworldly that appears as if out of the atmosphere. The figures emerge and disappear only to appear again. The work of revolution is slow, methodical work. It is vigilant. It is unyielding. The work of freedom never ends. It rages and wails, dreams and plans. It is an ellipsis that goes on for however long is necessary. Then pauses in the cavernous expectation of human will and infinite beauty. It waits in the shadows until you are ready to hear its call. It lingers, then trails off, knowing the signal it has left behind can be seen/heard by those in need. Like a sorrow song that moves from plantation to plantation seeking the listener attuned to the message in the call. I am. I am free.

Sisson’s Black Tears, like Ehlers’s Black Bullets, asks of the viewer that you take the time to contemplate the enormity of trauma sustained by black subjects on their way to getting free. For Sisson, there is this added detail: she is an associate professor at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. The same university where Borgquist was a student when he sent his letter to Du Bois one hundred and twenty years earlier. I asked Sisson if she knew about the letter and her response was “I must have.”29

Black Memory in the Interim

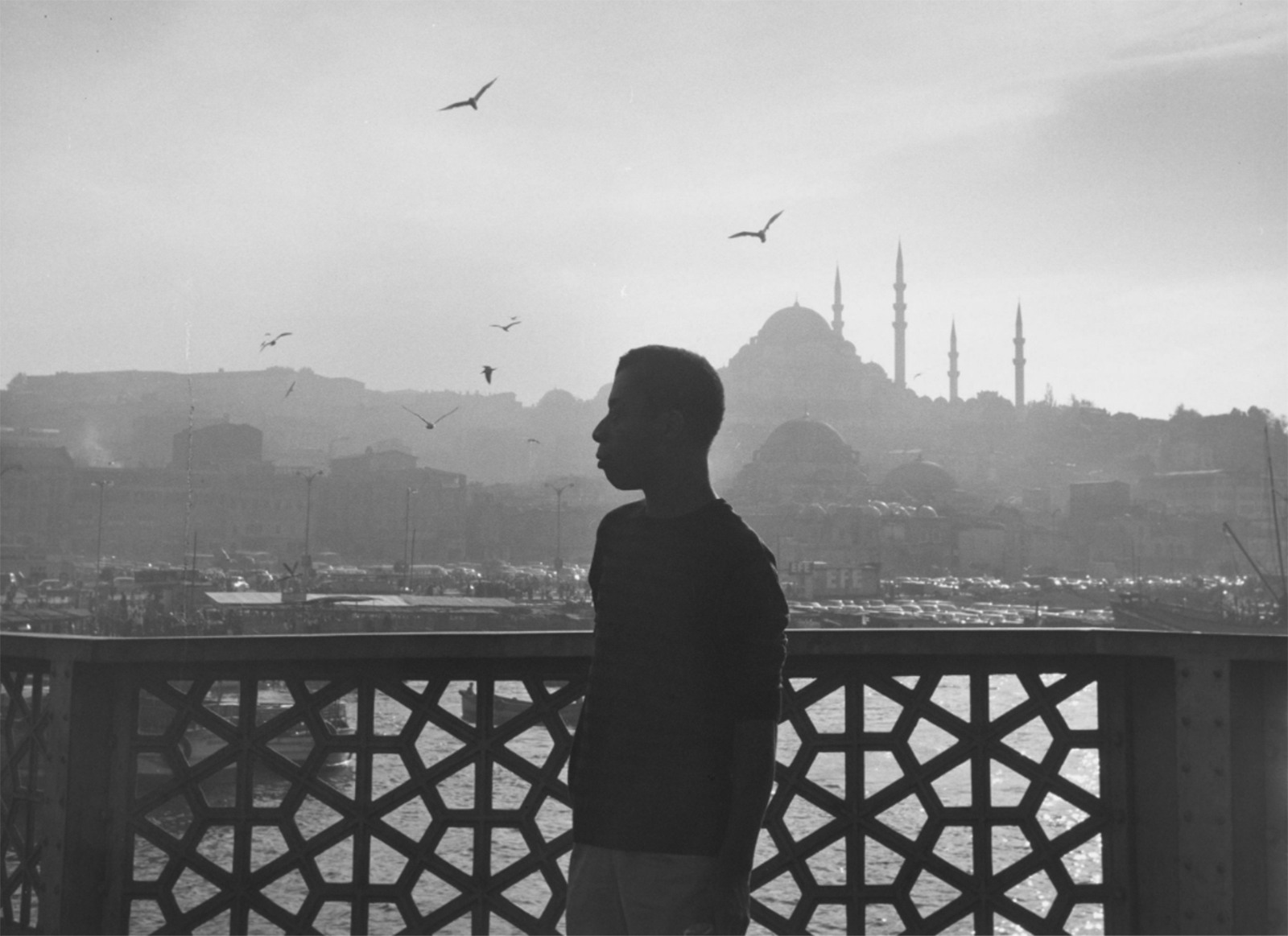

Soon after he arrives in Paris from the United States to put a measure of distance between himself and the country of his birth, James Baldwin is arrested along with a friend for the crime of stealing a bed sheet from a Parisian hotel. The arrest happens in the country that was to provide a kind of reprieve from the hypersurveillance, racism, homophobia, and criminalization Baldwin experienced in the United States. And so it is with a racially cognizant reading of his black presence that Baldwin marks the beginning of his decades-long negotiation of the self in public space.

After the publication of his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, and his essay collection Notes of a Native Son, Baldwin becomes a notable figure in the literary arts. Importantly, his artistic gifts are put in the service of deconstructing the racial order of the West, since, as a black American living in Europe, he has unique views about the work of antiblackness enveloping the world. Director Raoul Peck writes, “I started reading James Baldwin when I was a fifteen-year-old boy in search of rational explanations for the contradictions I was confronting in my already nomadic life, which would take me from Haiti to Congo to France to Germany to the United States.”30 Peck describes the impetus behind his painfully beautiful 2016 documentary about Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro. The relationship, violent and unyielding, between France and Peck’s native country, Haiti, is partially understood by reading Baldwin. Threading together articulations of power and conceit is something James Baldwin’s writings clarified for Peck. In the companion edition to the documentary, Peck continues: “What the four superpowers of the time did, in an unusually peaceful consensus, was shut down Haiti, the very first black republic, put it under strict economic and diplomatic embargo, and strangle it into poverty and irrelevance. And then they rewrote the whole story.”31 In this rewriting there are colonial powers with no dominion and imperial subjects with no past to recall or record. In the interim, though, black memory conjoins Peck and Baldwin in a discourse of the marginalized, and carries forth the language—literary and filmic, necessary for retrieval and repair.

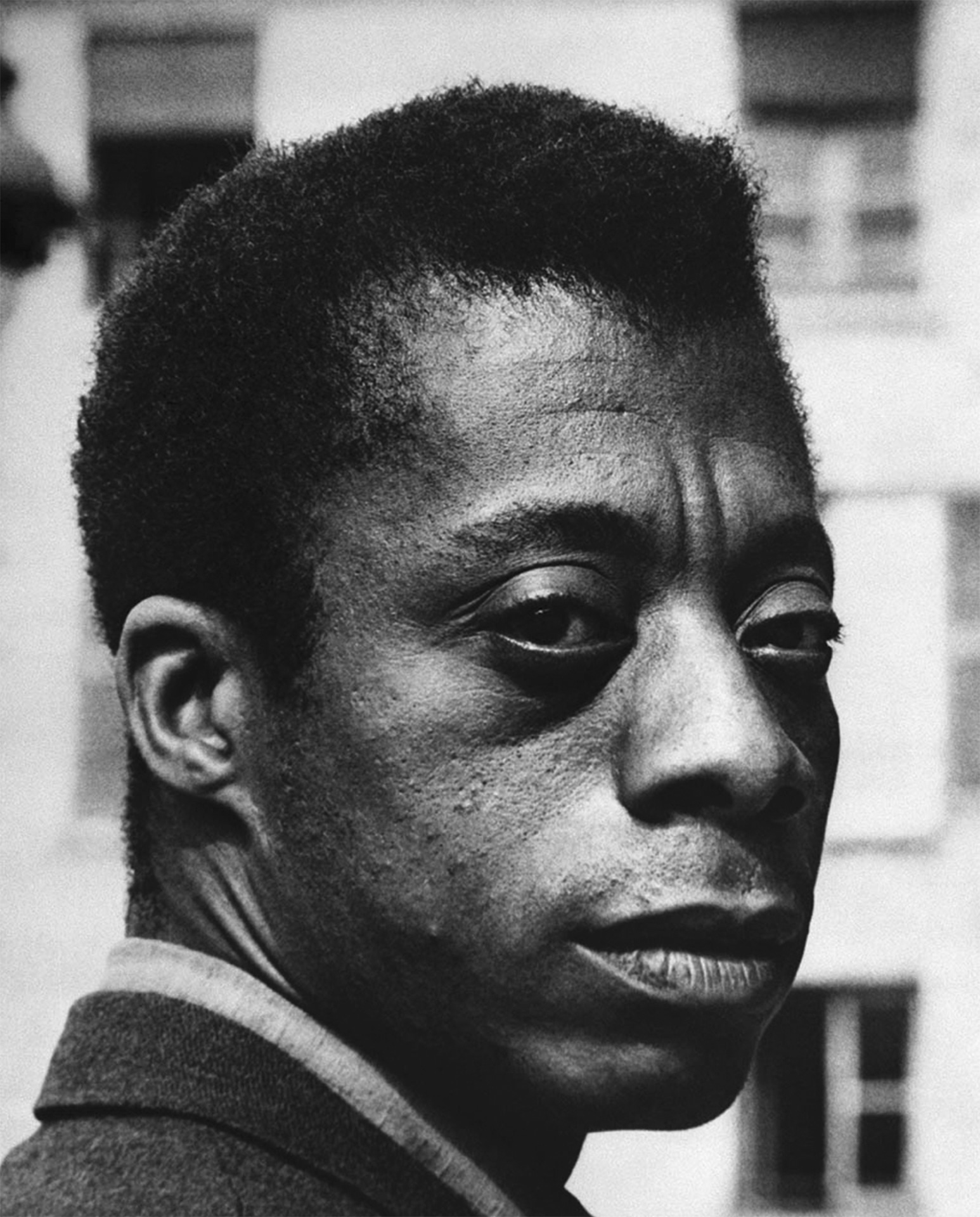

To the photographic eye Baldwin is the quest. Presence, loss, recovery, intensity, purpose, joy, and longing—all can be found in any photographic representation of James Baldwin. Unlike other artists, both brooding and brazen, Baldwin’s portraits seem less a construction of the man, and more an illumination of the force he was in the world. Part of this illumination is found in the simple visual display of Baldwin’s impressive subjectivity. His sense of his existence in this world, and what the world required of him in order to remain.

“My father said,” Baldwin writes in The Devil Finds Work, “during all the years that I lived with him, that I was the ugliest boy he had ever seen, and I had absolutely no reason to doubt him.”32 Baldwin finds this a damaging but not entirely unsurprising statement from his father. One encased within a paternity that did not belong to the man who raised him, but some other unknown man. He continues, “but it was not my father’s hatred of my frog eyes which hurt me, this hatred proving, in time, to be rather more resounding than real: I have my mother’s eyes.” In this statement we have the symbol and the referent, the mechanism of photographic engagement that hovers somewhere between resistance and refusal. Because for Baldwin, “When my father called me ugly, he was not attacking me so much as he was attacking my mother. . . . I thought he must have been stricken blind . . . if he was unable to see that my mother was absolutely beyond any question the most beautiful woman in the world.”33 With subtle flashes of visual perception, Baldwin marks his gaze in the direction of the maternal force he has summoned through the ocular: “I have my mother’s eyes.” And it is with these “eyes” that he sees above and beyond the range of vision offered to most.

The masculine and the feminine, the mother and the father, the yin enveloping the yang. This is the photographic world offered to us by James Baldwin, through the portraits that represent him and the visual structure of the narratives he produced. If photography is the studium in Roland Barthes’s universe, then James Baldwin is the punctum—he who punctures, wounds, illuminates, caresses. He who is both symbol and referent. “For the photograph is the advent of myself as other,” Barthes writes in Camera Lucida: “a cunning dissociation of consciousness from identity.” But Baldwin offers us no such dissociation. Baldwin’s ocular narratology mirrors the image we have of the man. It is a probing, resilient, precise exchange of gestures, theories, and intentions. The epitome of ocular verve. And so I want to think of Baldwin as the photographic image-maker who almost never took his own photograph. I want to think of him the way I think of the very best writers we know—as a visual artist—an author who mastered the art of the eye, the side-eye, the look, the look back, and the clap back. For every possible manner and modality of the human face and its awesome capacities has a James Baldwin ready-to-go expression. For he wore the great range of his emotive extensions on his face, in his eyes, and through his gestures.

This is a matter of the visual. To attend to the world of the seen and the spectacularly unseen. In this world and its inhabitants, designations and demarcations mark the trajectories of movement and imbue them with meaning. Baldwin again in The Devil Finds Work: “The root of the white man’s hatred is terror, a bottomless and nameless terror, which focuses on the black, surfacing, and concentrating on this dread figure, an entity which lives only in his mind.”34 Baldwin’s pointed critiques, his unrelenting eye for detail and interrogation have entered the archive of his repeated and sustained humanistic endeavors. Because we have the spectacular production of Baldwin’s engagement with the written word, it is possible the presence of Baldwin as visual interlocuter may need a bit of Baldwin’s own radical attention to detail. For it is Baldwin’s interaction with the world of the visual that most intrigues me, and tells me something about how he journeyed with grief in the frame of his visioning.

If we consider Baldwin within the expansive range of visuality and reckoning, his words carry over to discourses that negotiate the boundary marker of sight on sight. Between the religious rhetoric he frequently deployed and his deeply symbolic prose, Baldwin’s structured gaze facilitates an order of the world that contains him but doesn’t see him as he is. Baldwin’s lifelong dedication to the honesty and integrity of his true form ensured a particular way of seeing, a way of orienting his eye to the interiority he had and always trusted within himself. His eye. In the text for “Remember This House,” Baldwin writes:

The sky seemed to descend like a blanket.

And I couldn’t say anything,

I couldn’t cry;

I just remembered his face,

a bright, blunt, handsome face,

and his weariness, which he wore like his skin,

and the way he said ro-aad for road,

and his telling me how the tatters of clothes

from a lynched body hung,

flapping in the tree for days,

and how he had to pass that tree every day.

Medgar.

Gone. 35

Baldwin’s desire to be a catalyst of memory came at a cost to himself, particularly as he was scarcely given the time or the means to recover from each grievous loss, each death, every act of violence to which he was a witness or victim. If where does the grief go were a person, it would be James Baldwin.

From the moment he escaped the racist clutches of the United States to his multiple trips back, James Baldwin was a walking figure of mourning, rendered barefaced for all the world to see. It may seem to us now that he carried his grief well, and this is likely due to the constraints of time and the variations of movement allowed to take center stage. But from his first set of essays to his fiction and film criticism, Baldwin carried with him the full understanding of black life. A shadow figure stalking progress, antiblackness is the heavy load that Baldwin brings along with him everywhere he goes. Baldwin’s 1963 book The Fire Next Time has its opening addressed, in epistolary form, to Baldwin’s nephew and namesake James “on the one-hundredth anniversary of the Emancipation.” As he writes to his namesake, so does Baldwin write into and through himself, as a kind of cudgel against total despair. “You were born where you were born,” Baldwin writes. “And faced the future that you faced because you were black and for no other reason. The limits of your ambition were, thus, expected to be set forever.”36 Baldwin continues, “Wherever you have turned, James, in your short time on this earth, you have been told where you could go and what you could do.”37 Reflecting on his emergence as a child preacher at fourteen, Baldwin recognizes “I have never seen anything to equal the fire and excitement that sometimes, without warning, fill a church, causing the church, as Leadbelly and so many others have testified, to ‘rock.’ ”38 Ever cognizant of the power and force of sermons from the black church, Baldwin was able to incorporate his former life as a preacher into his writerly life.

The photograph of Baldwin holding an orphaned child in Durham, North Carolina, somehow renders with great potency the divergent and overlapping pathways of representation that Baldwin’s narratives evoke. Within the image there is the whitened figure of a biblical Jesus Christ, the symbolic register of Baldwin’s past devotion beckoning from a slightly elevated place of spatial proximity. There are the dozen photographs lining the bureau in assorted frames, an ever-present symbol of loved ones who remain at once removed and a part of Baldwin’s unique interiority. There is the child, abandoned, but momentarily held within Baldwin’s arms, looking comfortable but cautious. And there is Baldwin himself, appearing pensive and slightly distant. He is not facing the camera.

As this image in its cropped form graces the original cover of Baldwin’s 1963 masterpiece The Fire Next Time, it provides the viewer with another layer of Baldwin’s photographic reach. Structured as a letter written from Baldwin to his nephew and namesake James, the coupling of this child with this writer work to extend the intimacy of the familial beyond the photographic frame. “Ultimately, Roland Barthes writes, “photography is subversive not when it frightens, repels, or even stigmatizes, but when it is pensive, when it thinks.”39 Baldwin’s contemplative thinking in this image mirrors the thoughtful order of the gaze returned, so much so that the viewer is encouraged to think of the child as the personification of The Fire Next Time, since no image of an alternate Christ figure enters the frame, and Baldwin himself has refused the task.

An “abandoned child” is somehow the great subject of The Fire Next Time, always aware that there were other children nurtured, held, and loved, his very existence a reminder of all he has and will continue to see. And Baldwin in this photographic exchange highlights the shame of this without owning it outright. Because it is a shared shame, and every American citizen has to bear the markings of its structure. We can imagine James Baldwin in his multifaceted dimensionality: He is the cultural figure of the twentieth century: cosmopolitan, fluid, gifted, and rhetorically regenerating. He is the word and the flesh in the photographic imaginary. “When I was very young, and was dealing with my buddies in those wine- and urine-stained hallways,” Baldwin writes in The Fire Next Time, “something in me wondered, What will happen to all that beauty?”40

All that beauty. “For black people, though I am aware that some of us, black and white, do not know it yet, are very beautiful.”41 Something of Baldwin’s utilization of the photographic, knowing how photographs both highlight and obscure, is a reminder of the man in all of his full frontal insistence. If we take the iconography of James Baldwin as any indication, the writer is most prolific when he manages the mirrored constituencies of his artistic productions. He is, in his forceful yet relaxed photographic demeanor, the look, and the look away, the rhetoric and the reckoning, the symbol within the referent, and the eye on guard. All that beauty in one face within one gaze.42

He is a witness.

When I think about the modulations of grief located in black cultural productions beyond the genre of poetry, I think about James Baldwin’s long durée into the vicissitudes of black grief. In every essay, fictional rendering, interview, and poetic inflection Baldwin endeavored to calculate the total cost of black survival within and beyond the nation state. In this work I contemplate sites of mourning that do not register immediately as archives of grief: the landscape of a gulf coast property, the interior of a vehicle driven by a former friend, a quilt constructed out of clothing worn by a loved one, a film to mark a country’s reemergence after the defeat of slavery, a mural to mark the forced removal of a group of people. To these examples I add James Baldwin’s unfinished book manuscript, “Remember This House,” upon which Peck’s documentary is based. I’m cognizant of Baldwin’s elongated black memorial processes that, with aesthetic precision, encompassed multiple black diasporas under one worldview. In doing so, Baldwin’s public persona serves as a central force with which to reckon, and this, of course, is bound by great loss.

Baldwin places three murdered black American men, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. in conversation, “as a means of instructing the people whom they loved so much, who betrayed them, and for whom they gave their lives.” Along the way, the film coheres around Baldwin’s significant powers of observation, which he utilizes to lay claim to anger amid deep, racial grief. “That’s when I saw the photograph,” Baldwin writes of a walk in Paris. “Facing us, on every newspaper kiosk on that wide, tree-shaded boulevard, were photographs of fifteen-year-old Dorothy Counts being reviled and spat upon by the mob as she was making her way to school in Charlotte, North Carolina. There was unutterable pride, tension, and anguish in that girl’s face as she approached the halls of learning, with history, jeering, at her back. It made me furious, it filled me with both hatred and pity, and it made me ashamed. Some one of us should have been there with her!”43 Understanding, as he does, the calculous of the collective in the face of racial terror, Baldwin wishes for proximity, for the intentional impetus of protection that numerical isolation does not allow.

For Baldwin, then, it was not just racial animus that compels him to speak, but the racial isolation that makes blackness its own kind of marker for others to further deepen an insistence upon violence. On “colorblind” racial policy in France, Trica Keaton writes, “Raceblind republicanism, justified in the name of equality, thus becomes a form of national gaslighting on matters of racism’s production of race, and those who question the ‘normalcy’ become identified as the racists.”44

In a telling interview from 1970 with Terence Dixon, for the short documentary film Meeting the Man, Dixon describes what he considers to be a recalcitrant Baldwin, refusing the directives offered, and ignoring suggestions the documentarian has made. What you find, in a twenty-seven-minute arc of increasingly agitated discourse, is Dixon’s disregard for the writer he has come to interview. His questions, which sound more like accusations (“You do spend a lot of time between novels, why is that?”), are meant to diminish Baldwin’s power as an artist and political figure. Instead, they illuminate the writer’s stunning brilliance amid astounding grief.

This grief, as ever-present as it is resounding and palpable, is often illegible to others even when Baldwin goes to great pains to make clear the stakes of his humanity. After Baldwin answers the “time between novels” question, he adds, “I must point out, though, too, that I’ve been working the last few years between assassinations. . . . I mean, they’re killing my friends, it’s as simple as that. And have been all the years I’ve been alive.” To this devastating admission that Baldwin has been “working the last few years between assassinations,” Dixon moves with the speed of flat affect on the road to deflection. “Why don’t you just want to get away somewhere and sit down and write your books? Why don’t you want to do that?” “Because I am better than that,” is Baldwin’s response.

Dixon But you don’t have to be better than that.

Baldwin Oh, I do.

Dixon So you don’t agree, then, I mean, when people say, “Oh, it’s okay for him. He’s escaped”?

Baldwin What . . . have I . . . escaped? 45

That Dixon struggles to grasp the gravity of “they’re killing my friends. . . . And have been all the years I’ve been alive” is telling. He moves quickly on to the business of “escaping,” perhaps hoping that Baldwin will allow this movement to stall the flow of his mournful considerations. He does not. But what if Dixon had been able to stay with Baldwin’s directive, to pause as he had and allow the air to hold Baldwin’s grief and rage in place? What if instead of Dixon’s flat affect and quick dismissal we had an actual engagement with the writer’s pain? What if Dixon could imagine that?

Baldwin’s memorial production, the ebb and the flow of his gestural, expressive, contemplative visual display, is part and parcel of his engagement with the world of the visual. To encounter Baldwin’s prose is to delve beneath the depths of human frailty and foreclosure. It is to consider the primacy of the visual as it orients the lives and labors of the citizens it refuses or holds close. To think of Baldwin, then, as the country’s foremost theorist of race and the visual is to place him within the canon of interlocutors without whom we would have no contemporary discourse of visuality. His powers of observation were the enduring result of measured, potent analysis, cultivated over the course of many years, through several literary genres and in every imagistic presentation of the man.

If we consider Baldwin within the expansive range of visuality and reckoning, his words carry over to discourses that negotiate the boundary marker of sight (ocularity) and site (location). Baldwin’s structured gaze in both documentaries facilitates an order of the world that must take his grief along with it. Baldwin’s lifelong dedication to the honesty and integrity of his art making ensured a particular way of seeing, a way of orienting his direction to the interiority he had and always trusted within himself. His eye.

And Baldwin is most vocal about the loss that has shaped so much of his life as a writer, and as a black man. It is the loss of his country, though this is a loss he chose in order to save his own life. “In the years in Paris,” Baldwin writes, “I had never been homesick for anything American . . . all of these things have passed out of me. . . . But . . . ,” he continues, “I missed Harlem Sunday mornings. . . . I missed the music, I missed the style—that style possessed by no other people in the world. I missed the way the dark eye closes, the way the dark eyes watch, and the way when a dark face opens, a light seems to go everywhere. I missed, in short, my connections, missed the life which had produced me and nourished me.”46 This longing takes on profound shape as Baldwin sutures his interiority to the black world-making that first made him a diasporic subject a long way from home.

Grief and Survival

As a contemporary example of both grief and mourning impulses, and an elegy to those who have survived this, the protagonist in Toni Cade Bambara’s short story “The Survivor” embodies a space of traumatic contradiction. Consumed by the severity of an abusive spouse and the memory of her fraught black urban existence, the protagonist Jewel’s impending motherhood is a source of suppressed agony for her. In the story, the young actress is a repository of unwanted memories and although she is precious, as her name implies, she is unable to access the better parts, the jewels of herself. That which she is forced to remember renders her emotionally stifled, and these remembrances are at once vibrant and unrelenting. They include:

Brother Billy on a dare leaping blindfold from a cliff in Morningside Park. The aged super, her friend over the checkerboard, being removed from the cellar on a dingy stretcher, starved to death, left to wait on the curb while the attendants grabbed a smoke and she shrieked, impotent. Carl Berry, who early, tenderly, gave her to herself, walking off the roof—the final high. Great grandaddy Spencer with emptied eyes strapped down under the rubber sheets as they turn him on like Frankenstein and she had signed and he had begged but she had signed.47

Feeling helpless and unable to escape the past or to process her own personal horrors, with “the mind off guard, an easy mark for all the one part dreams three fourths forgot,” Jewel spends her days floating through time.48 She manages the extremities of her personal and familial pain by drifting in and out of each painful memory she harbors in her psyche and gives birth to when her emotions demand it. Bambara tautly handles the impossibility of black survival, both self and other, without the assistance of the community to bring Jewel back from the brink of total destruction.

When the story begins, Jewel is on her way to visit her “grandmother,” a woman who goes by many names. “And it was Miss Candy again, M’Dear, Other Mother as the young nieces and nephews called her, no one else.”49 For Jewel, Miss Candy is safety as well as torture, since Jewel is not in control of her memories and visiting Miss Candy has a way of triggering the buttons that lead to undesirable flashbacks: “Wives, she’d learned growing up in the dark, were the ladies found tied to scuttled boats at the bottom of the lake, their hair embraced by seaweed.”50 Jewel’s interior battles, played out stylistically in the narrative by the unconscious memories placed in italics, guide the reader through the impending madness of the story’s heroine. Emotionally bereft, physically exhausted and psychologically damaged, Jewel meanders through the narrative a tattered remnant of her former self, and yet only her subconscious mind attempts to understand why. Jewel continues, imagining,

Husbands were men with their heads bashed in, doused with alcohol, stuck under the driver’s wheel, and shoved over the cliff. . . . Wives were victims pushed beyond endurance, then snatched suddenly back from the edge by that final straw we carry from birth just in time to butcher beer bellies in the bedroom. Husbands were worms that turned on the femmes fatales who were too cocky to plot his death and got strangled with piano wire 51

Jewel’s tormented and abusive relationship with Paul, her lover and the director of the movies she stars in, takes center stage in the narration as Jewel attempts to wrap her mind around his demise in a car accident, her third-trimester pregnancy and the mental disease making itself present in her psyche. Theirs is a desperate, physical, and psychological enslavement, mimicking love, and their unborn child is at the center of their relational madness. During one of their many disagreements, Paul informs Jewel of his plans to move to a hotel room temporarily, and in return “she found herself leaning on the breadknife, asking the arbiter below her ballooning breasts if she may take the giant step.”52 Bambara creates in “The Survivor” a protagonist’s journey that is impossible to navigate, as it bears down on the multisensory alignments of violences Jewel must endure. In the interim, the new life emerging seemingly has nowhere to go without absorbing everything that has come before it. “Black women’s lived experiences,” writes Juliet Hooker, “complicate how we think about agency.”53

Paul’s presence in the story is overwhelming, as Jewel refuses to see him in the past tense. She revisits moments of their frantic togetherness searching for images of her former self, the self which she no longer is. Throughout the story they elude her and she must settle instead for the half reality “coiled in her memory, springing at the last, seizing her at the casket and spinning her right around to hurl her into the collapsible chairs and up under the flowers, smothering.”54 The filmic display of Jewel’s disintegration compels through the thickened narrative of imagistic bombardment. “There were ghosts in the kitchen,” Jewell imagines. “She had stumbled aware of some night visitation that would reveal its purpose if she could wait.”55

Although motherhood is not something that Jewel outwardly resists, the narrative casts a troubled shadow on Jewel’s pregnancy, signaling a maternal resistance that emerges through flashes of slow madness. As Jewel travels to Miss Candy’s on a bus, “she shifted her weight, not so much to balance the baby, as to juggle the mind’s dangers, to ease the shouting in the head less it become a banging on the wall—let me go mad, Grandmother. Let me bleed and be forever lost and no-one.”56 Jewel desires a psychic purgatory where she can be no one instead of making someone. In her quest to slip into nonexistence, Jewel desires an escape that can ease her of this lifelong pain her impending motherhood would only extend. She embodies the complicated agony presented by cinematic representations of black womanhood. But Jewel is as unable to articulate her pain as she is to alleviate it. She journeys through her gestational torment as if she will be able to see her way through it in a fog, as if she will give birth to herself and not another being who will pull her further apart.

Miss Candy will be the midwife to Jewel’s unborn child, guiding the young woman from embattled selfhood to disrupted motherhood. This is another kind of haunting, where reality is the “refrain that cuts to the core of the relationship between black feminism, precarity, and futurity,” according to Tina Campt.57 While Jewel is in labor, the final part her emotional stability takes leave and she drifts deeper and deeper into insanity. Drawing on her memories of Paul’s direction and her screen acting, Jewel conflates her labor with a wrenching scene she must perform with her lover’s help. The story ends tragically, as Jewel makes her descent into the world of fantasy and proves herself unfit for the motherhood she embodies. Following a succession of contractions,

Jewel didn’t let on that she was awake and spying. She watched the ancient dwarf pull the creature glistening with seaweed out of her left thigh. She watched them smile at the thing and then at her. The smile that meant if you didn’t plan carefully, you would be destroyed. It was best to play the scene out with a few lines and bide her time.

Nurturing her dysfunctional relationship for years, dealing with the continuous decay of her community and immediate family, Jewel is a woman broken. Her physical and emotional breakages, slow, steady, and harrowing, are now her metaphorical offspring. Pain has been her only constant—the ever-deepening companion. The creative and inquisitive mind that once served as her artistic force has been transformed into a paranoid remnant of its previous self. “The Survivor” implied in the title of the short story is not Jewel, nor is it her soon-to-be-born child. What ultimately survives in the narrative is trauma-as-haunting—that which the reader is left to contemplate. She doesn’t just see ghosts, she is one, and in this becoming it is impossible for others to rescue or recognize her. Thus, as a woman burdened and overburdened, raised by a surrogate mother, Jewel’s journey comes to a debilitating close while she alone ponders the place of her baby, “the metallic monster in the mud encasing” that she feels she must destroy in order to free herself.

“The Survivor” asks the reader just how much black people—black women—can bear, how much they can create after trauma, and what is left after the trauma remains. In a series of narrative film clips moving from one space of fractured existence to another, Jewel is unable to see beyond her embodied stasis. And she finds it impossible to move on. So the story ends with a dissociative episode, where Jewel leans into her fractured psyche in order to make it to the next stage of her “survival.”

Calida Rawles’s 2019 painting Radiating My Sovereignty features a female figure floating in aquatic serenity, as water envelops the visual field. Both buoyed and gliding, Rawles imbues the image with a glistening ethereality that black subjects rarely receive in art or in life. The artist’s large-scale realist-abstract creations provide the viewer with the unique opportunity to imagine blackness in its liquid configuration, with flashes of free-flowing movement accelerating the glow. These images glide as they flow, and signal release from the ties that bind one to the present or the past.

In Alvin Ailey’s memorial to black women and mothers, Cry, a single dancer takes center stage for nearly twenty minutes dressed all in white. Originating in 1971, Cry was a birthday present for Ailey’s mother with Judith Jamison in the starring role. It has survived as one of Ailey’s more enduring choreographies, routinely performed to this day. As a ballet, it is known for the toll it takes on the performer of the dance. The difficulty of performing Cry is legendary, with dancers remarking on the bodily endurance necessary to complete the performance successfully. As an allegory of black women’s tribulations in the country, Cry is a visual test of resilience even as it celebrates that resilience cloaked in mourning. For Jamison states, “Exactly where the woman is going through the ballet’s three sections was never explained to me by Alvin. In my interpretation, she represented those women before her who came from the hardships of slavery, through the pain of losing loved ones, through overcoming extraordinary depressions and tribulations. Coming out of a world of pain and trouble, she has found her way—and triumphed.”58 More than this, Cry symbolizes an understanding of the relationship between embodiment and mournful release, particularly in the realm of triumphant survival. Cry was produced in a few weeks by Ailey, illustrating the force of intention the choreographer deployed. DeFrantz writes, “Cry ends with the dancer center stage, performing a full body dance of divination. Tearing at the earth and sky simultaneously, she moves in unabashed ecstasy, embellishing subtle variations in rhythmic accent with her hands, shoulders, and feet as the curtain falls.”59 Cry, as an expression of embodied grief, binds, contorts, and retreats in an effort to break free.

Lucille Clifton’s poem reply provides an answer to the question posed by Alvin Borgquist so many decades earlier regarding “whether the Negro sheds tears.” To this she responds, “he do / she do / they live / they love / they try / they tire / they flee / they fight / they bleed / they break / they moan / they mourn / they weep / they die / they do / they do / they do.”60

We do.

Note 1

Letter from Alvin Borgquist to W. E. B. Du Bois, April 11, 1905, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, https://credo.library.umass.edu/cgi-bin/pdf.cgi?id=scua:mums312-b001-i301, archived at https://perma.cc/6L2Q-RBJB; emphasis added.

Note 3

Charles Rowell, “I Have Never Looked Back Since”: An Interview with Roy DeCarava, Callaloo 13, no. 4 (Autumn 1990): 864.

Note 12

Martin Luther King Jr., “Eulogy for the Young Victims,” n.d., https://vimeo.com/34762047, archived in part at https://perma.cc/X454-CGVZ.

Note 16

Randy Kennedy, “Roy DeCarava, Harlem Insider Who Photographed Ordinary Life, Dies at 89,” New York Times, October 28, 2009.

Note 17

Darby English, How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007), 6.

Note 21

John Tagg, The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 1.

Note 22

Ivor Miller, “If It Hasn’t Been One of Color”: An Interview with Roy DeCarava,” Callaloo 13, no. 4 (Autumn 1990): 851.

Note 24

Faith Smith, Strolling in the Ruins: The Caribbean’s Non-Sovereign Modern in the Early Twentieth Century (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023), 8.

Note 25

Jessica Lanay, “To Know Your Family So Specifically: Jeannette Ehlers Interviewed,” BOMB Magazine, December 14, 2021, 4, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2021/12/14/to-know-your-family-so-specifically-jeannette-ehlers-interviewed/, archived at https://perma.cc/GX23-MN3E.

Note 26

Robert Hayden’s poem “Frederick Douglass” refers to “freedom” as “this beautiful and terrible thing, / needful to man as air.” Hayden, Collected Poems (New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, 1985), 62.

Note 27

Sault, “I Am Free,” 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C44BAmw1K5k, archived in part at https://perma.cc/QL3X-WAAK.

Note 28

Sault, Untitled (God) (Forever Living Originals, 2022); Jeannette Ehlers, Black Bullets (video still), 2012.

Note 29

In a text message to the author from March 2023, Sisson wrote: “There is so much connection across time and place . . . the Black Tears continue to surface again and again.”

Note 30

James Baldwin, I Am Not Your Negro (New York: Vintage International, 2016), viii. A companion edition to the documentary film directed by Raoul Peck and based on texts by Baldwin.

Note 42

Glenn Ligon’s 2000 screenprint Untitled (Crowd/The Fire Next Time) uses Baldwin’s poignant question as the framework of his layered meditation on the Million Man March, which took place in Washington, DC, in 1995.

Note 44

Trica Keaton, You Know You’re Black in France When: The Fact of Everyday Antiblackness (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2023), 10.

Note 45

Terence Dixon, dir., Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris (Buzzy Enterprises, 1970).

Note 47

Toni Cade Bambara, Gorilla, My Love (New York: First Vintage Contemporaries Edition, 1992), 99.

Note 53

Juliet Hooker, Black Grief, White Grievance: The Politics of Loss (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023), 201.

Note 58

Judith Jamison quoted in “Cry,” https://www.alvinailey.org/performances/repertory/cry, archived at https://perma.cc/3FP4-7CNY.