Introduction: Grief in the Atmosphere

An obituary is for the public, a lament is for the community.

—Teju Cole

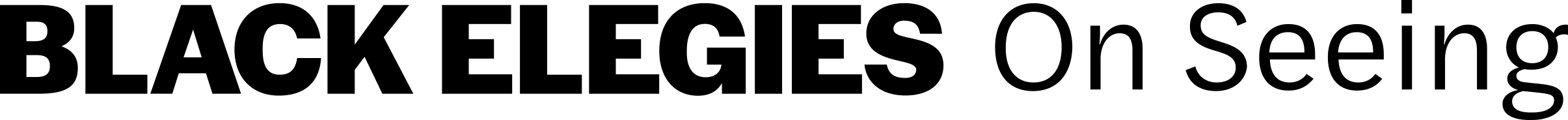

Out of the darkness, up from the ground, bodies draped in earth tones, move. Slowly, with arms outstretched, they reach up, hands open: an offering, a prayer, an archive, an elegy. Alvin Ailey’s ballet Revelations brings African American culture through its meditative and linear history, affixed to the music that has instrumentalized black life in the reservoir of the larger world. For Thomas DeFrantz, “This image of bodies rooted to the floor while faces are directed upward confirms a choreographic motif of split focus that permeates the dance. These are people in physical bondage invoking, though their movements, spiritual deliverance.”1 The spirituals that wrap and lace Revelations do so through black church familiarity and sonic potency. Beginning with “I Been ‘Buked and I’ve Been Scorned” and “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel,” “Wade in the Water,” “I Wanna Be Ready” and ending with the boisterous “Rocka My Soul (in the Bosom of Abraham),” Revelations “began as a staged enactment of the choral singing of spirituals.”2 Thinking of Revelations in this way, as movement through the recesses of enslaved mourning and music, gives the performance its requisite gravity. With a pitch-black background, dancers of different shades assemble in unison, spinning out through portals of collective interiority and exhibiting the multifaceted enactments of forced improvisation.

Revelations is performed in three sections: “Pilgrim of Sorrow,” “Take Me to the Water,” and “Move, Members, Move.” Each section marks a distinct moment in African American history from enslavement to religious salvation and freedom of movement. Ailey’s choreography encompasses angular movement with wide jumps and expressive, muscular gestures. The performance exemplifies bodily stamina and grace, resilience, beauty, and the elegance of purpose, what Ailey referred to as his “blood memories.”3 Blood memories are born with you, are born in you, and set your directional body dial in the arena of creative extraction that falls under your control.

Sorrow songs, or spirituals, are one such illustration of the cultural production of forced improvisation. Like other manifestations of black art originating with captives from the transatlantic slave trade, sorrow songs developed as expressive sonic venues of release for black subjects, holding the horrors of the experience together with motifs of survival. Improvisatory in its construction, “Antiphony (call and response),” according to Paul Gilroy, “is the principal formal feature of these musical traditions. It has come to be seen as a bridge from music into other modes of cultural expression, supplying, along with improvisation, montage, and dramaturgy, the hermeneutic keys to the full medley of black artistic practices.”4 Revelations offers this “full medley” in mournful lows and spiritual highs, in a measured hint of corporeal retrieval that reckons with losses so expansive and violent that it would take land and ocean to begin to navigate its breadth. Its reach.

John Coltrane’s masterpiece A Love Supreme is an all-consuming sonic conjuring that trips over the frame of four suites in thirty-two minutes and forty-seven seconds. A Love Supreme is spiritual transcendence, the arc of human existence, a love story, an elegy. Like the brilliant architecture of a jazz monument to God, Coltrane exceeds the boundaries of what is possible musically, materially. In four stages of sonic evolution, the listener is treated to the four planes of Coltrane’s movement: Acknowledgement, Resolution, Pursuance, and Psalm. These nuanced stages of black ecstasy and black grief end in the repetition of a chant of survival: a conjuring of the sort that inspires, redeems, anchors, and retrieves. A love supreme . . . a love supreme . . .

Of all the jazz musicians emerging out of the U.S. South in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, Coltrane is the one most steeped in the cloak of grief, cloaked in an understanding of loss, longing, and black retrieval. “Sound is not ideologically neutral,” Ren Ellis Neyra writes. “Sound manifests in the shapes made in captivity, and from bodies that exceed the state’s self-sovereign and antiblack epistemologies.”5 Coltrane exceeds the frame of sound shapes made within and beyond captivity, in the outer reaches of black embodiment that metaphysically command a place at the table where grief also resides. “In all jazz, and especially in the blues,” James Baldwin writes, “there is something tart and ironic, authoritative and double-edged . . . only people who have been ‘down the line,’ as the song puts it, know what this music is about.”6 The music, as Coltrane imagines it, as he performed and deployed it, is about mourning. And the ghostly matters that lead to mourning as a form of release. Coltrane was in a meditative and contemplative space when he created A Love Supreme. Elliott H. Powell notes that “Coltrane’s iteration of the other side of things involves addressing life events of the present (e.g., sadness) and transforming them for a better future world (e.g., happiness).”7 What Powell refers to as Coltrane’s “queer sonic eccentricity” is connected to James Baldwin’s auditory retrievals. In both men, the cadence of grief was ever present, and constantly connected to their way of moving though the world.

In Baldwin’s first published nonfiction book Notes of a Native Son, the title essay appears in the center of the text as the author guides the reader through his processes of mourning while engaging in the difficult work of being black in America and beyond its borders. Published in 1955, Notes is Baldwin in his narrative arc, composed of ten essays that range from literary and film criticism to his personal thoughts on his evolution as an African American writer born and raised in New York City. The essay “Notes of a Native Son” begins with the catastrophic convergence of Baldwin’s father succumbing to illness on the same day that Baldwin’s sibling is born. Further, Baldwin tells us, “The day of my father’s funeral had also been my nineteenth birthday,” marking life, death, and renewal in the same space where he grapples with all the restrictions on his humanity that he has experienced in his short time on earth.8 Of his father Baldwin writes, “He had lived and died in an intolerable bitterness of spirit and it frightened me . . . to see how powerful and overflowing this bitterness could be and to realize this bitterness was now mine.”9 As we know, Baldwin was able to delve into the difficult intricacies of emotion with the precision of a surgeon. But I think we fail to consider all this cost him, even as his writings offered the world a path through the steel portals of rage and grief that often stalk black life. “The dead man mattered,” Baldwin declares at the end of his “Notes of a Native Son” essay. “The new life mattered; blackness and whiteness did not matter; to believe that they did was to acquiesce in one’s own destruction.”10 In all the ways that matter, Baldwin used his voice to hold in regard that which could easily be lost in the hierarchy of cultural refusals and racial animus. Attuned as he was to the cadence and rhythm of black life, Baldwin’s profound gifts were held in place in order to keep black people alive and offer some solace to those lost. “I can’t be a pessimist,” he says in a clip from director Raoul Peck’s recent film I Am Not Your Negro, “because I’m alive.” Baldwin continues, “To be a pessimist means that you have agreed that human life is an academic matter. So I’m forced to be an optimist. I am forced to believe that we can survive whatever we must survive.”11 In a series of essays and interviews, in a four-part jazz tribute, or a dance performance marking the trajectory from captivity to freedom, black elegies are everywhere. In this book I want to consider artistic representations of black grief as part of the extended discourse of the poetic elegy, telling us something about meditations of loss. In these instances of elegiac deployment, it is within the atmosphere of national refusal and dispossession that artists and writers do the scaffolding work of mourning while black. Part of this scaffolding work includes imagining spaces for grief where it might be possible to acknowledge the violence that attends black life.

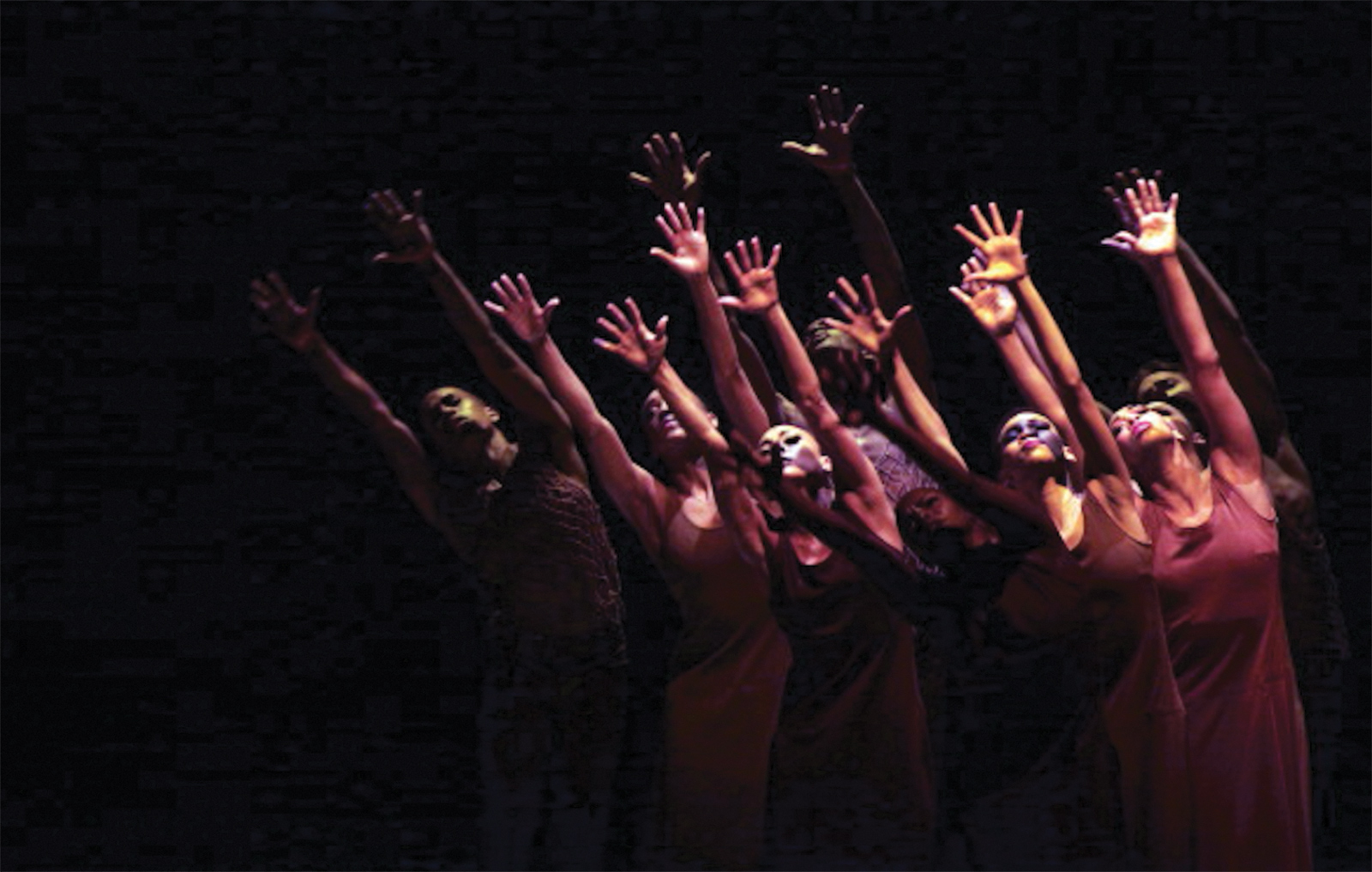

Mary Lee Bendolph, one of the famous Gee’s Bend quilters from Alabama, is known for her sophisticated and elegant quilts. Bendolph created Ghost Pockets from her husband Rubin Bendolph’s old clothing. Created in 2003, ten years after Rubin’s passing, Ghost Pockets is Bendolph’s way of holding Rubin close—close enough to touch—with strips of clothing he wore when he was alive. With the deepened indigo outlines (the ghosts) of denim pockets as markers, Ghost Pockets displays lines of red with bursts of yellow, purple, and gray. The quilt deploys a haptic materiality, which soothes and consoles, all with the tactile consistency of touch. African American quilt traditions emerged during and after slavery, when enslaved workers would collect scraps of discarded fabric used to make clothing and stitch them together in order to craft a bedcover/blanket to keep warm in the colder months. This particular form of utilitarian improvisation has led to an art practice that involves geometric abstract design alongside bold strips of color. Ghost Pockets is imbued with a painterly inheritance while participating in the mourning processes of black grief. The importance of creating a tactile object of memory making, one that highlights the retention of the person remembered, is connected through the stitching in a visual display of sporadic ghost pockets that serve as reminders of that which was lost. Elegies direct the line of communication from the living to the dead and back again. They take many forms. “I don’t believe in ghosts,” Tiya Miles writes. “Not really, not rationally. But this did not stop me, on a damp winter night in 2012, from going in search of one.”12 I, too, am on a search for ghosts, or at least the haunting residue of their presence. To be a researcher of transatlantic slavery leaves one few alternatives than to travel among ghosts wherever they take you. I visited my first slave plantation in 2010, and it was Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. The ghosts there haunted me, have stayed with me ever since.

My first trip to Monticello was a solo journey. And it was harder than I even imagined it would be. I remember sitting on one of the benches on the property after the tour and feeling the heaviness of the space, even while I was surrounded by a kind of boundless admiration for Jefferson that did not fit the gravity of what I was experiencing. I was also the only black person on the tour, which was surprising to me. There were awkward glances from other visitors to the plantation, as if the only thing standing between them and their enthusiasm for the property was my dark brown body signaling a link to enslavement. The second time I convinced my friend Shirley to accompany me from New York to Virginia so that I was not alone. The third time I visited the plantation I brought my friend Vanessa as a witness. By my third visit to Monticello, I was deliberately looking for ghosts—or at least my own personal haunting.

Ghosts occupy space and time, requiring our attention. In fact, depending on where you are you may be directed by one, and ordered to do its bidding. Perhaps what the ghost wants is recognition, perhaps vengeance, and maybe even a little bit of their own grief to carry. A ghost who wants nothing does not exist. Think of it that way. To enter a time and space—a room—a park—a temple of worship—an alleyway, is to confront the there that came before you. An ancestor, a kindred spirit. To speak to you and often through you, so that you are in communion with the living and the dead while you are here. We could call it purposeful synesthesia.

To enter a time and space—a room—a park—a temple of worship—an alleyway, is to confront the there that came before you.

“I don’t believe I am synesthetic,” Teju Cole writes. “But I cannot always account for the intensity of my sensations.”13 Synesthesia, as Cole describes it, is a way of navigating multiple sensory experiences simultaneously. Black cultural productions privilege a heightened relationship to the sensorial, often enacting a deepened feeling as part of the process. Black Elegies is attuned to the subtle overlap of the sensorial that is imbued with immersive properties of sight, sound, taste, and touch. This subtle overlap is the interest of this book, and so I have chosen texts that exceed the frame of their emergence to tell us something about what happens in that overflow. Texts like Revelations enact a kind of mirage of feeling that goes beyond mere performance to expose something new, something elongated and inscribed. Some of the choices I make here illustrate my way of seeing and feeling, and therefore emerge from my particular vantage point. I hope you move with me as I make sense of my choices along the way. My mandate has been simple: If I think it is an elegy, then I pursue this possibility, and I follow the winding road to see where it may take me. I ask that you take this ride with me in the hope that we may find communion in the arc of creative intention before us. In this way, sight is a visual navigation that arrives to inform the haptic, and sound is a way to see beyond the delineations of discovery most immediately available for subjective experience. Black elegies, then, employ a poetics of the sensorial that indexes and archives the synesthetic potency of the form. My aim is to use a poetics of loss to manage the canyon of beauty and grief in multimodal forms of elegiac expression.

This book is one way to commune with ghosts—of nations, people, histories, and the past. It is a weaving of examinations of fiction, film, poetry, and photography. It depends heavily on the musicality of longing and loss. It flows, like water with “perfect memory” from one purposeful expression of grief to another.14 “We die,” Toni Morrison writes in her Nobel Prize-winning speech. “That may be the meaning of life. But we do language,” she continues. “That may be the measure of our lives.”15 Black elegies tarry where statistics skew precision of loss, where slippages between there and here expose the fallacy of temporality. “Sometimes we summon our ghosts; sometimes our ghosts are a constitutive part of ourselves,” Habiba Ibrahim writes. “At other times, our ghosts lovingly pursue us, and lovingly unmake us.”16 For what is a ghost story but a way to see into the abyss of what is already there? So conjured, so called. Be they duppy, banshee, ghost, or haint, they signal the thing that remains after loss: people, land, country, or culture. They demand that we give space for grief or they will take it without permission, like a momentary wind knocked out of you as you travel along your day.

(After the murder, after the burial)

Emmett’s mother is a pretty-faced thing;

the tint of pulled taffy.

She sits in a red room,

drinking black coffee.

She kisses her killed boy.

And she is sorry.

Chaos in windy grays

through a red prairie.

A quatrain reminds the reader of the lift that rhyme can bring to poetry. This one, from Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem “The Last Quatrain of the Ballad of Emmett Till,” upends this expectation.17 To the promise of musicality embedded in the ballad, Brooks mutes this lift so that it lands in elegy. So that it does the work required of grief in the dark, where somber tones tell another story. Did the directional pull of black elegies have to find another way? Did the demands of opacity dictate the terms of engagement? Did black lives find a way to redress the needs of an ever-expansive collective? Part four of Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, Psalm, meanders around his tenor sax, what Michael S. Harper refers to as “the tenor kiss, tenor love,” stretching out the length of the section like a lover yearning for the lost touch of the beloved.18 Or the pinnacle of glory that prayer and practice have held out as a promise to the initiated. “Emmett’s mother is a pretty-faced thing; / the tint of pulled taffy. / She sits in a red room, / drinking black coffee. / She kisses her killed boy. / And she is sorry. / Chaos in windy grays / through a red prairie.”19 Brooks weaves a sonic quatrain out of images of sharp color that define Mamie Till’s mourning process as she seeks justice for “her killed boy.” The poet lets us into the arena of longing as it is tethered to a Chicago mother’s grief for the son violently taken during a summer spent with relatives down south. Till is not the first child taken with such violent intention in the United States or beyond and he will not be the last.

When Carrie Mae Weems creates a series of silkscreened panels, each featuring the name and statistical details of those black subjects killed by law enforcement officers, she couples the information with archival pigment prints swathed in deep blue. These ghostly figures haunt the frame as they exceed it, drawing out the navigation of racial violence though the multiple bodies it will claim. The images themselves are mesmerizing, not simply due to Weems’s stunning atmospheric control, but also due to the momentary (and lingering) iteration of familiarity in each of the frames. We both know and can never know these people. This familiarity haunts, because in large part what we encounter is the fading image of a black subject not fully seen, but assumed, dismissed, surveilled, and redacted. Blurred blue and out of focus, Weems has rendered them unavailable for capture, made visually poignant since the viewer gets to participate in their temporal escape. Figures both present and absent, real and imagined, captured and fugitive. In the thickened blue that absorbs and releases them, Weems has created haptic possibility. Images more tethered to touch than sight, and distributed visually as still images in movement, in mourning.

Weems’s recent series Slow Fade to Black offers an earlier precursor to The Usual Suspects. In Slow Fade to Black Weems blurs images of iconic black stars of stage and screen, placing them out of focus and into a kind of blurred anonymity. This blurred anonymity in turn is a kind of elegy, for it allows the viewer to contemplate the full measure of access and visual aggression that stalked women from Billie Holiday to Katherine Dunham, Mahalia Jackson, and Nina Simone. As each woman is exposed to the gaze of the viewer, they are simultaneously rendered unavailable for such scrutiny, leaving only a hint of their visual availability behind. The Usual Suspects removes clean visual availability in favor of a thick, blue immersive engagement that is at once haunting and familiar. This project moves between the haunting and the familiar, choosing to illuminate the wonder located there. In this, I trust the reader may also engage in discoveries, which, like a strip of bright red in a field of gray may surprise and delight, settle and soothe. Like a ghostly sorrow song with a double meaning or a photograph gloriously presented large and bold, but out of focus. These ghosts, with their demands and commands, open sensorial capacities so that layering or conflation can occur, leading to something like ecstasy. An ecstatic retrieval where sight, sound, smell, and touch are heightened so that an immersive experience consumes the body, leaving it susceptible to the encounter to come.

There are constitutive elements in the manner of black grief we must grapple with. When I specify “black grief” I am thinking about an enclosure of blackness that must continually resist the violent atmospheric presence of antiblackness. Christina Sharpe writes, “Anti-blackness is pervasive as climate. The weather necessitates changeability and improvisation; it is the atmospheric condition of time and place; it produces new ecologies. . . . When the only certainty is the weather that produces a pervasive climate of anti-blackness, what must we know in order to move through these environments in which the push is always toward Black death?”20 Sharpe’s investigation of the heavy burden placed on black subjects takes into account the many ways that black life has resisted and continues to resist the violence of antiblackness.

So, along with all the ways that black subjects live and die, there are the sensational and arbitrary acts of extreme violence that spectacularize death in ways that do not allow for the dignity of grieving, privately or otherwise, without hypervigilance on the part of the survivors. Survivors are my investment with Black Elegies, not just those who have survived a loved one who has passed on, but also survivors who negotiate losses that do not end in death: losses like distance, homeland, diminishment, and the absence of care that often accompanies racialized subjects everywhere they go.

And they go. Carried by histories and memories that frame their relationships, connections, and ways of being in the world. They move, like ripples on still water, marking place and subtly changing the elements around them. They grieve, seen or unseen in the light of day or the dark of night. They create, in the vibrancy of human experience and spiritual will. What if we paused to spend time with the gravity of these gestures? What if we were to hold them close, like a love object in an unfolding scene sutured to black life?

Black Art, Black Grief

Dawoud Bey’s Elegy conjoins ghosts and atmosphere in a series of black-and-white photographs that bring black grief into stark visibility. A mixture of portraits and landscapes, the images range in meditative potency while surprising the viewer with flecks of presence, of place. In binding people to land, to foliage, and to the aquatic, Bey simplifies the understanding of black American culture so that it emerges from the ground (with indigenous recognition) and flows outward on bodies of water headed nowhere. Headed everywhere. A mixture of earlier and more recent works, Elegy is Bey’s love poem to black aliveness, to black survival, black memory and longevity. His 2017 gelatin silver print Untitled (Lake Erie and Sky) is a line on the horizon bringing the heavens to the brim of Lake Erie to tell a different kind of ghost story. Something foreboding this way comes, as viewers are entangled in a web of recognition that demands stasis. You are to take your time here. That is the demand. There is no way to quickly disperse a ghost.

Steve McQueen’s 2015 photograph Lynching Tree is a seemingly innocuous tree set deep in a Louisiana forest. McQueen found the tree while scouting locations for the 2013 film he directed, 12 Years a Slave. The tree’s overgrowth hides the bodies of victims of lynching in the enclosure of its own foliage. Like water sanitizing a crime scene. The fraught relationship between black subjects and the land that sustains and often claims them is McQueen’s visual concern. And in the way that the land makes those claims, people have natal stories that tether them to place, giving them a sense of history, family, legacy, and continuity. Haunting in its anonymity, the lynching tree nevertheless indexes its horror, since any tree, north to south, east to west, can be utilized as a violent framework of subjection. Its gestural composure allows for both possibilities to exist in the same place and time: peace and horror.

Ebony G. Patterson’s 2018 Three Kings Weep produces this duality in a video triptych featuring three finely clothed and bejeweled black men moving in slow motion. The three-channel video projection allows the viewer to hold the men in their gaze as they slowly remove layer after layer of clothing while tears well up in their eyes. Three Kings Weep is overlaid with references to Claude McKay’s famous poem “If We Must Die.” The intensity of the gaze combines with raw vulnerability wherein the men cry openly while not averting that gaze.

Visual art as memorial, as elegy, traverses the world of the living and the dead, the grieving and those to be grieved. In this suture between the loved and the mourned, grief coheres around the palpable recognition of existence that is held in place.

Curator Okwui Enwezor’s Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America exhibition addressed what he called “the crystallization of black grief in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance,” as one way the 2016 U.S. presidential election marked a “commitment to white supremacy.” Before his untimely death in 2019, Enwezor put together this exhibition and catalog examining “modes of representation in different mediums where artists have addressed the concept of mourning, commemoration, and loss as a direct response to the national emergency of black grief.”21 Black grief as a national emergency is an alteration from previous discourses on black life or black death. The indifference that meets black subjectivity, the hypervisibility and surveillance, reinforce the disposability of black subjects in a contemporary visual framework. It is with Enwezor’s prompt that I want to consider “the national emergency of black grief” as a way to attend to mourning practices in art and literature that engage the discourse of elegy both within and beyond the genre of poetry.

In this suture between the loved and the mourned, grief coheres around the palpable recognition of existence that is held in place.

Somewhere along the way to completing my latest book project it occurred to me that I was in the process of writing two books. Mortevivum: Photography and the Politics of the Visual concerns the relationship between documentary photography and histories of antiblackness. For Mortevivum I examine images of the dead and dying in the media in order to measure the space of visual possibility foreclosed for black subjects on the cusp of the twenty-first century. Black Elegies contemplates sites of mourning that do not register immediately as archives of grief: the landscape of southern U.S. slave plantations, a spontaneous street performance, a quilt constructed out of the clothing worn by a loved one, a ballet to hold the memory of black history, an aeolian harp installed at an institute of European art.

Here, in the repetitious refrain of the sorrow song, in its current alteration and temporal elongation, it cannot be appropriated for whom it is not intended. For a circular formation modulates, with incredible vocal control, the cavernous wall of grief that is black. Without a nod to the universal. Resonance. Vibration. Reverberation. Echo. In the full embodiment of this rendition of the sorrow song/ spiritual “Motherless Chil’” by Sweet Honey in the Rock we hear the amplified extension of the mournful loss of the familial illustrated in so many works of the black diaspora. I want to think through the sonic life of Black Elegies here, with a few thoughts about the cadence and order of slavery’s perpetual haunting, its unyielding and generational lament. “Motherless Chil’” is, for me at least, of the thousands of sorrow songs written, sung, and reproduced by unnamed and uncredited slaves in the United States, one that emphasized the distance between over there and over here. That profoundly violent and repetitive extraction of children from their mothers gave slavery a cruelty beyond human calculation and a horrifyingly corporeal precision. “The most universal definition of the slave is a stranger,” Saidiya Hartman writes in Lose Your Mother. “Torn from kin and community, exiled from one’s country, dishonored and violated, the slave defines the position of the outsider.”22 In this a cappella version of the popular sorrow song “Motherless Chil” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, arranged and with lead vocals by Carol Maillard, slight alterations in the lyrics extend the discourse of slavery and motherloss beyond the boundary marker of slavery’s extended geography. Black subjects must both cross the ocean and also somehow embody it. They must reproduce and be reproducible. They must labor without an end on the horizon. And what they create will be taken from them. Though they represent the profound loss of the motherless child and its natural corollary, the childless mother, they alone live with the trauma of this event. And they must do all of this within a very limited rubric of possible release. And therein lies the vibration. The resonance. The echo. The reverberation. The repetition. And the call. Sight, sound, and touch extend the trauma of the Middle Passage beyond the bodies and the territories it encompassed. For those who made the journey are dispersed and not often remembered. They labor and love “a long way from home” and negotiate the sliver of space between over here and back there. Sorrow songs provide the guidepost to the elegies explored in this book. They appear as a particularly American genre, coming from enslaved workers on plantations in the U.S. South. That we have thousands of spirituals preserved from the nineteenth century speaks to the horrors of slavery in the United States as well as the efforts put forward to create something beautiful out of the devastation this has caused.

Of Elegies

Within the genre of poetry dedicated to addressing the depth and breadth of loss, the elegy has a long and vibrant history, particularly in the United States. Black elegies, though, have a less secure space in American literature. In a problematic racial canon that often takes mourning as a white presentation, elegies are often bereft of black poetry but full of a poetics of black mourning. For instance, the cover image of Max Cavitch’s book American Elegy: The Poetry of Mourning from the Puritans to Whitman features a photograph of African American twin boys, one of whom is dead. In the visual dissonance of the cover image we can see the process of black elegiac refusal at work, as a book of literary criticism that has almost no mention of black grief utilizes an image of palpable black loss as its central visual symbol. Black twins, one living, one dead, both offered up as objects of emotion, not for themselves, but to assist in the expression of (assumed) white grievers. How did African Americans become located outside processes of mourning readily available to others? What is there to understand in the refusal to acknowledge the existence of black grief? Black Elegies considers the expansive range of cultural productions that move in sight, sound, and touch, like sorrow songs with double meanings. My project coheres around the concept of elongated grief that is the residue of trauma African Americans and other diasporic subjects experience due to the history of slavery, empire, and racial violence in the nation and beyond its borders. This history of violence necessitates multivalent approaches to the properties of mourning that assist in alleviating some of the pain of existing while black.

Elongated grief may look like a fictional narrative about a pregnant film actress whose body cannot sustain the life held within her, because she has reached the end of a violent horizon with no end in sight. It may look like a cinematic exchange where the gaze enraptures its protagonists as if letting go would be the end of everything they know. It might sound like an instrumental accompaniment to a eulogy for girls killed in a church explosion. Or it could feel like the unfinished manuscript by a writer who was never at a loss for words. Black Elegies moves with and beyond disparate iterations of artistic mourning to uncover the deepened frequencies of loss, as that which is discernible is not always all that is there.

Chapter 1 of Black Elegies, “Sight,” deploys the visual to access avenues of recognition that allow black subjects to envision processes of mourning as inclusive of the gaze. I’m interested in works that grapple with the space between visuality, loss, and subjectivity. In this case the gaze is a way to regard from a place of mutual understanding. Chapter 1 features work from Roy DeCarava, Jesmyn Ward, Alvin Ailey / Judith Jamison, Toby Sisson, Toni Cade Bambara, Jeannette Ehlers, and Toni Morrison. Chapter 2, “Sound,” relates to the relationship between black mourning and the sonic. Black sonic practices range from sorrow songs and sermons, to film renditions, fiction, and poetry. Chapter 2 concerns the sonic life of loss and includes works by Kahlil Joseph, Vievee Francis, Jennie C. Jones, Marvin Gaye, Amanda Russhell Wallace, and Saidiya Hartman. Chapter 3, “Touch,” engages the haptic gravitational pull of touch that creates its own enclosure of catharsis, moving from one bereaved black subject to another. Chapter 3 examines works from Toni Morrison, Dell Marie Hamilton, Carl Phillips, Barry Jenkins, Audre Lorde, Rebecca Hall, and Michelle Cliff.

Black Elegies considers the expansive range of cultural productions that move in sight, sound, and touch, like sorrow songs with double meanings.

I am purposely resisting the desire to encapsulate black mourning processes around Sigmund Freud’s important essay “Mourning and Melancholia,” since his meditation on the contours of grief cannot be easily grafted onto black diasporic subjects whose profound losses precede Freud’s intervention by two hundred years and continue still. I am asking different questions for this book project. A constant question that circulates around Black Elegies is “where does the grief go?” And the answer is everywhere. It spills out of photographs and modulates music. It hovers in the tenor and tone of cinematic performances. It resides in the body like an inspired concept, waiting for its articulation. Grief is an ocean. It is an abyss. To quote Toni Morrison, it has no beginning, no end, just circles and circles of sorrow.23 And the loss is tectonic, covering the surface of the earth while moving, shifting, sliding, and expanding. From sorrow songs, wood carvings, and deeply meditative spiritual sermons, to essays, photography, music, and film, black subjects have mourned what was lost even when not recognizable as loss. This book aims to highlight the center of gravity that is black grief. My intention is to spend time exploring the myriad ways black subjects attempt to live and mourn in and out of plain sight.

Note 1

Thomas DeFrantz, Dancing Revelations: Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 6.

Note 3

“Celebrating Revelations at 50,” 2010, New Jersey Performing Arts Center, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=44nqeAXLS-k, archived in part at https://perma.cc/2NM5-NFBR.

Note 4

Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993), 78.

Note 5

Ren Ellis Neyra, The Cry of the Senses: Listening to Latinx and Caribbean Poetics (Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press, 2020), 58.

Note 7

Elliott H. Powell, Sounds from the Other Side: Afro-South Asian Collaborations in Black Popular Music (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 27.

Note 12

Tiya Miles, Tales from the Haunted South: Dark Tourism and Memories of Slavery from the Civil War Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 21.

Note 13

Teju Cole, Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021), 173.

Note 14

Toni Morrison writes, “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” From Morrison, “The Site of Memory,” in The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations (New York: Knopf, 2019), 243.

Note 15

Morrison, “The Foreigner’s House,” in The Source of Self-Regard, 106; emphasis in original.

Note 16

Habiba Ibrahim, Black Age: Oceanic Lifespans and the Time of Black Life (New York: New York University Press, 2021), 183.

Note 17

Gwendolyn Brooks, “The Last Quatrain of the Ballad of Emmett Till,” in Blacks (Chicago: Third World Press, 2000), 340.

Note 18

Michael S. Harper, Dear John, Dear Coltrane (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1970), 75.

Note 20

Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 106; emphasis added.

Note 21

Okwui Enwezor, Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America (New York: Phaidon Press, 2020), 7.

Note 22

Saidiya Hartman, Lose Your Mother: A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2007), 5.

Note 23

Toni Morrison’s novel Sula ends with Nel’s realization that she had for all those years been missing her friend. Her resulting cry “had no bottom and it had no top, just circles and circles of sorrow.” Morrison, Sula (New York: Knopf, 1973), 174; emphasis added.