Coda: Grief in the Dark

If I tried to write a universal novel, it would be water.

—Toni Morrison

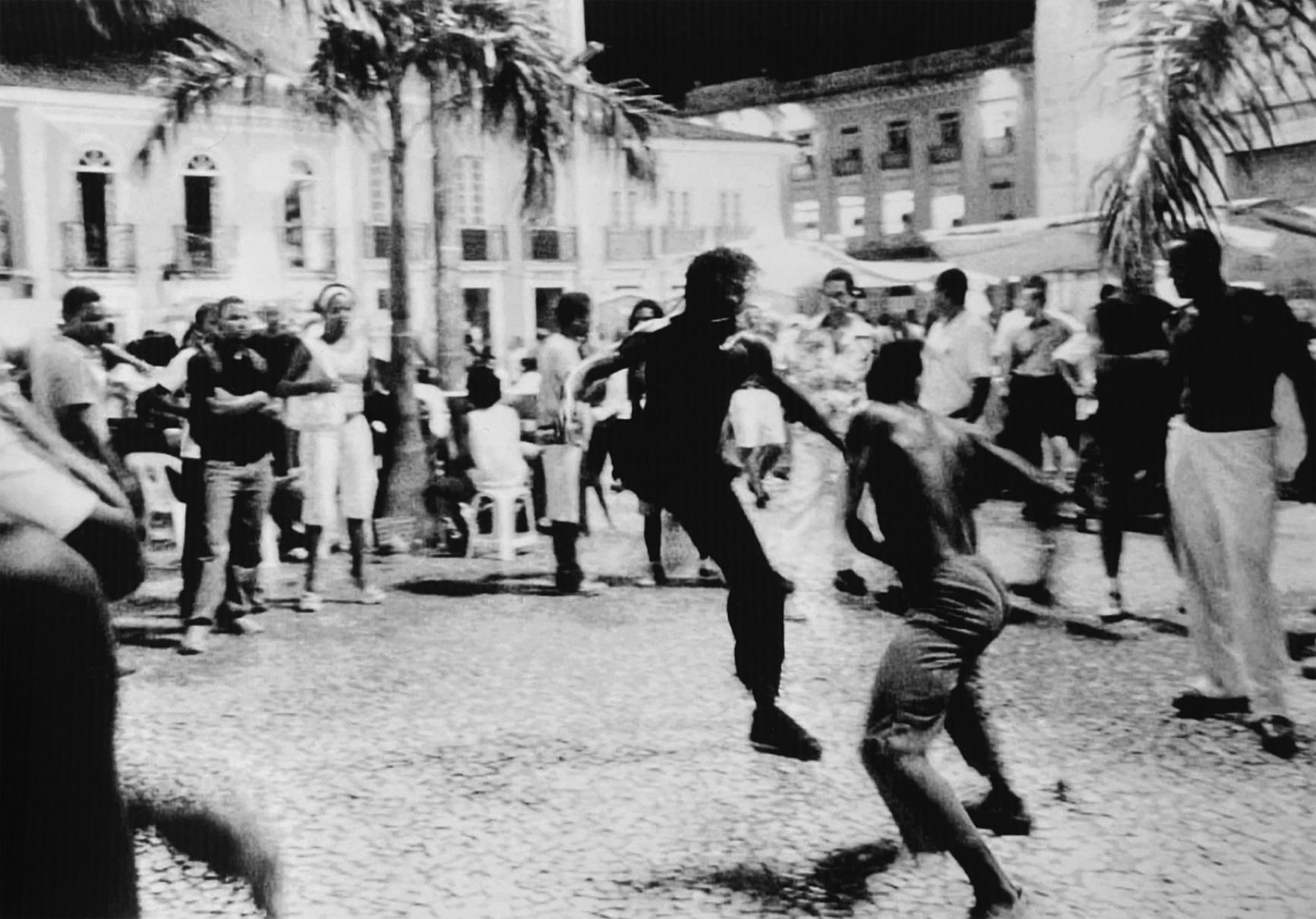

One body moves in sync and in time with another. Together they bend to the arc of the wind and the sun. The attendant percussion, its rhythms and heartbeat swell with the flow of the crowd. Be it large or small, the energy of the crowd illuminates and heightens the work taking place. The Brazilian art of capoeira, one-part martial art, one part dance, is the work of forced improvisation—a hybrid negotiation between resistance and symmetry. It makes proximate the violence of touch without reproducing the violence of that touch. Intimate and elegantly coordinated, the practitioners bring their bodies into conversation with the grief that abides enslavement, and aids survival.

If we can glean, in the almost-touch of capoeira, the boundless resistance of the sorrow song, the drumbeat/heartbeat of ecstatic release, we will have some sense of the measure of corporeal response located here. It feels like witnessing the coexisting energies that feed off each other, and then into the crowd around them. A force field created in its ephemeral production, and encircling those in want, those in need.

The origins of Brazilian capoeira are located in Angola, and are transported to Brazil via the transatlantic slave trade that the Portuguese originated in the fifteenth century. We know much about the violent dehumanizing process of Portuguese enslavement, and how aggressively it was maintained—until the cusp of the twentieth century, no less—but individual and collective acts of resistance are embedded in the sights and sounds of the nation. Even more so in the inscribed movements of the tens of millions of descendants of the transatlantic slave trade whose geographical endpoint from Middle Passage ships was the South American colony of the Portuguese empire.

In Salvador da Bahia, former capital of the nation of Brazil, on the edge of the Bay of All Saints, there sits a lasting monument to the long legacy of slavery that we still don’t fully understand in its totality. But all the senses converge in Salvador, if you are paying close enough attention. And all the sounds respond to the cacophony of grief encircling its atmosphere. Lá, in the center of the bustling city, on a lake forged from the past, orishas standing twenty-two feet tall conjure souls. They float, with armor and shield, closer to the heavens from which they source their power. They rise, like the undead, from the body of water that formerly held a seventeenth-century dam. So, for nearly four hundred years of Portuguese imperialism this aquatic center held the secrets and now reveals them in the circular formation of a protective ecstatic shield. The first slave market in the new world, the site of a military embankment, the resurrection site for Yoruba deities, and the spiritual heartbeat of the nation, Salvador da Bahia is also home to the remnants of sugar plantations that signal the country’s previous relationship to the source of its early wealth. And in the motions and movements of Brazilian art and dance, we see the residue of forced improvisation rendered artistically.

Like a sorrow song with a double meaning, slavery’s temporal boundaries and geographic portals teach us how to navigate the after of this violent before. In the Caribbean and South America, cultural retentions combine with New World mourning rituals to help keep black subjects from drifting into despair. An entire universe of catharsis and control, ritual and memory is produced through the wonders of creative expression that are tethered to this history. Though I have mostly focused on the United States in my exploration of these elegies, we know how expansive this productive extension is because the Atlantic Ocean, that vast waterway that invented the black diaspora, is its most defining feature.

Dionne Brand writes, “Water is the first thing in my memory. The sea sounded like a thousand secrets, all whispered at the same time. In the daytime it was indistinguishable to me from air. It seemed to be made of the same substance. The same substance which carried voices or smells, music or emotion.”1 Water as ecstatic elixir, which facilitates the verisimilitude of flow—flow as glide, as sway, as air-guided journey that moves, in the words of Lucille Clifton “from this to that.” In its temporal elongation the ocean, the sea, has stood as elemental witness to the vagaries of humanity, as its relationship to life has been investigated, drained, poisoned, and pillaged. “All beginning in water. All ending in water,” Brand reminds us. In its endurance and malleability there is much to discover, much to discern. In the molecular composition that is two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen, an entire world exists. For the expansive range of movement embedded in the oceanic we understand “the sea was its own country, its own sovereign.”2 The sea beguiles and hypnotizes, meanders and remains. In order to grapple with its potency and its special contours, attention must be paid to the black diasporic reference points that are made in its name. And in its wake. The sea encompasses humanity’s original declaration of existence, and by inference, its end.

Before I made my way to Thomas Jefferson’s plantation home, I visited Salvador da Bahia for research. The whole city is a merging of slavery, spirituality, music, grief, and celebration. As a resonant “city of the dead,” Brazil, according to Joseph Roach, “derives from its ghostly power to insinuate memory between the lines, in the spaces between the words, in the intonation and placement by which they are shaped, in the silences by which they are deepened or contradicted. By such means, the dead remain among the living.”3 In Salvador da Bahia, the dead and the living cohere in order to shape the memory of slavery and mourn in plain sight. What the landscape and terrain of slave plantations in the United States offered, Brazil does through the Atlantic.

In its temporal elongation the ocean, the sea, has stood as elemental witness to the vagaries of humanity, as its relationship to life has been investigated, drained, poisoned, and pillaged.

When Salvador de Bahia’s famous musical group Didá Banda Feminina emerge to perform on Tuesday evenings in Pelourinho’s central square, their audience is engaging with the visual remains of Portuguese slavery. Each member of the Afro-Brazilian group appears wearing an outfit replete with the image of the slave deity Blessed Anastácia across her chest, her symbolic violated and enslaved body serving a cultural and historical purpose. As the young women move, their drumming, singing, and dancing bodies work in silent dedication to a powerful historical enigma. As Afro-Brazilians wrestle with slavery’s unmistakable intimacy with death, Anastácia gives them visual appeasement. The slave woman is offered up as an entity able to transcend her earthly body for the benefit of all who descend from slavery’s racialized underclass. The visual image of the deity, taken from a nineteenth-century sketch by a French traveler, shows the contemporary incarnation of collective intention. Whereas Jacques Arago drew the figure of a male slave being punished in Colonial Rio de Janeiro, Brazilians over a century later witnessed a miracle of gender transference in flesh and image when they found the sketch in a museum in 1968. She is their creation. They have yet to let her go.

Pelourinho is a Brazilian Portuguese word that means pain—slave pain. Translated as “pillory,” there is the remnant of a whipping post in the central square of the former capital city that now negotiates the physical terrain of deities and dancers, imagery and memory. This project, despite its preoccupations, is not about death, but rather an examination of the denial of vulnerability negotiated by black Atlantic subjects since antiblackness is routinely made palatable so that the past continually informs the present. This is a phenomenon that takes place rigidly and repeatedly on black bodies, like the musicians who enter Pelourinho’s center every Tuesday evening, mere steps away from one of Brazil’s more successful slave markets and torture stages. The musicians face their audience carrying the grief of the violent embodiment of the past, informed by deep, abiding loss.

And so, though I made my first journey to Brazil searching for the pinprick of slavery’s remains, I left consumed by the specter of ghosts. I saw faces that so resembled my own they felt like kin. I watched movements of bodies that seemed steeped in a kind of unspoken understanding, a ballet of dark recognition. I spent days gazing out at the Atlantic and finding a kind of soothing unease, as if I had been drawn to the water in that particular space so my body could feel the waves against my skin. Waves that felt like loss, felt like home, and felt like love.

Waves that felt like loss, felt like home, and felt like love.